After breakfast at the RYSE, we took the bus over to Changgyeonggung, the palace next to Changdeokgung. After spending the morning there, we visited Gwangjang Market before visiting Jongmyo. We ended the day back at Hongdae for dinner.

Morning

After waking up at the RYSE, we had our usual breakfast buffet in the hotel restaurant. After breakfast, we decided to take the bus to 창경궁 Changgyeonggung as there is a convenient bus stop right by the palace entrance. The bus stop at Hongdae is also very convenient as it is almost right in front of the RYSE.

The bus route passed by in front of 광화문 Gwanghwamun. We then passed by the 동십자각 Dongsipjagak where we saw one of the pink Hechi themed busses that runs on the 남산 Namsan route.

Changgyeonggung

After getting off the bus and crossing the street, we were in front of the 홍화문 Honghwamun, Changgyeonggung’s main gate.

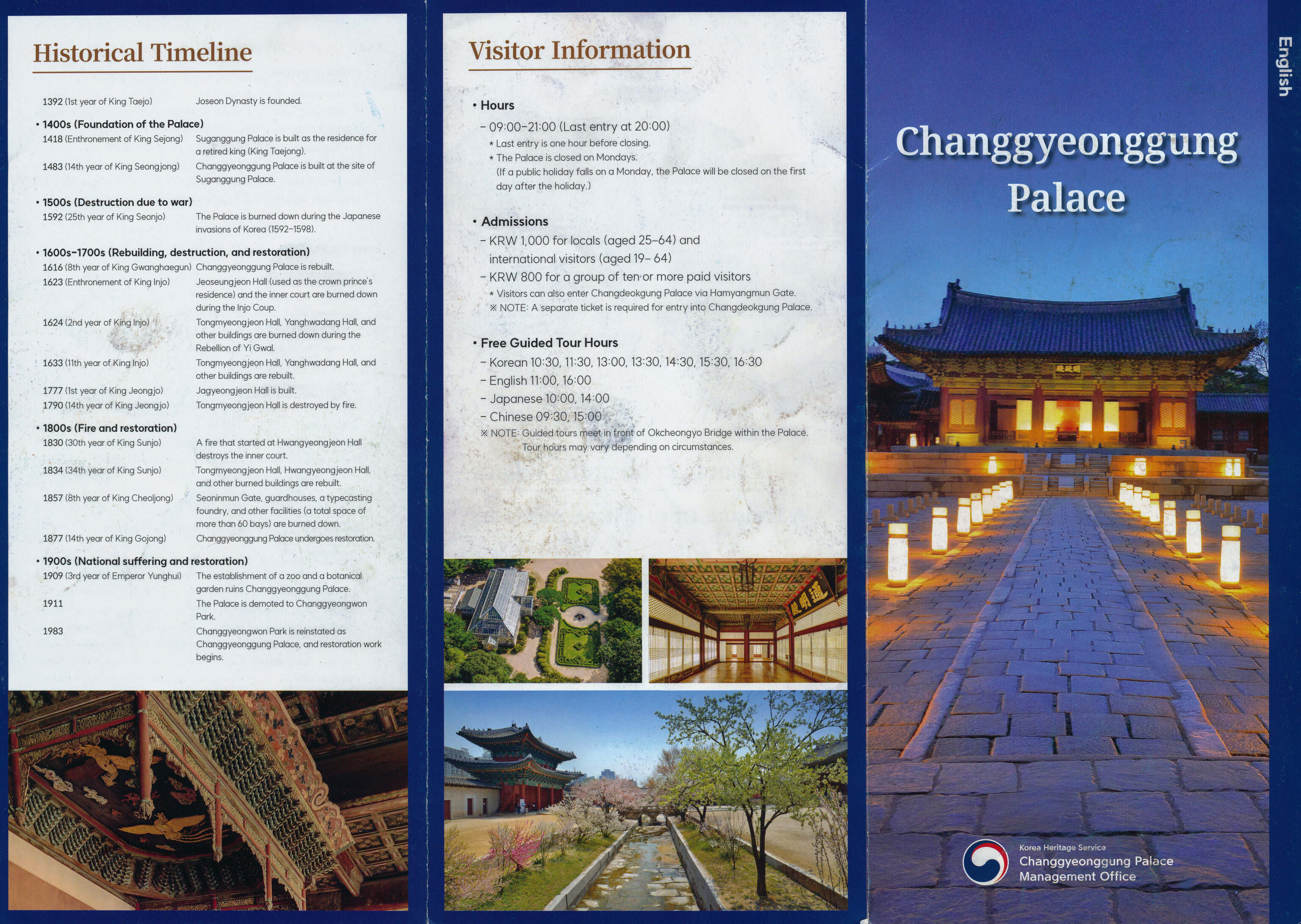

We picked up an informational pamphlet with map on our way in. A sign describes the large courtyard beyond the gate:

The main gate of Changgyeonggung Palace, Honghwamun, faces east, like the central part of the palace. It was built in 1616, and it was here that the king received ordinary people. Military examinations were held outside this gate. Hamchunwon Hill, now on the grounds of Seoul National University Hospital, was an archery range. Although the gate was unassuming for the gate of a royal palace, a pair of Sipjagak pavilions were built on the right and left in order to uphold the standards of a palace gate. Inside the gate, Geumcheon Stream and Okcheongyo Bridge served as a symbolic entry courtyard.

The Okcheongyo Bridge, mentioned on the sign, is just beyond the gate. The palace website has a description of this bridge (#2):

Built in 1484, Okcheongyo Bridge means 'a flowing river as pure as a jade marble.' In reality, clear water coming from Eungbongsan Mountain flows towards the south of Okcheongyo Bridge passing Jondeokjeong Pavilion of Changdeokgung Palace and Chundangji Pond of Changgyeonggung Palace. This bridge remains intact and designated as National Treasure No. 386. Under the arch of this bridge, goblin face is carved. This means protecting the palace against evil spirit coming through the river.

This well worn stone sculpture is on the bridge.

Looking back from the bridge, we had a good view of the Honghwamun.

Just ahead, we could see the 명정문 Myeongjeongmun, the gate leading to the next courtyard to the west.

We noticed what seems to be a covered well next to the stream.

The courtyard beyond the Myeongjeongmun leads to a courtyard containing the 명정전 Myeongjeongjeon, the throne hall of the palace. A sign describes this courtyard.

Rebuilt in 1616, Myeongjeongjeon Hall is the throne hall of Changgyeonggung Palace. It is the oldest of the throne halls in the remaining palaces in Seoul. Although it is a simple, one-story structure, it was built on a two-tiered elevated stone platform to give it the dignity suited to the main hall of a royal palace. The courtyard in front of Myeongjeongjeon was covered with wide, flat, rectangular stones. Running through the courtyard is a three-lane path, the center reserved for the king's use, that accentuated the sense of dignity of the palace. To the rear of this area was a corridor connecting it to other palace buildings. The courtyard is enclosed by Myeongjeongmun Gate and the cloisters running around the entire area. The cloisters were used by the royal guards or for preparations for royal funerals.

We looked back at the Myeongjeongmun as we walked through the middle of the courtyard to the Myeongjeongjeon.

The Myeongjeongjeon is built upon an elevated stone foundation. This slight increased elevation allowed us to see more beyond the Myeongjeongmun.

Like all the other similar halls in Seoul, we weren’t able to enter the building. But, we could look in from the main door as well as on the sides. It is a very familiar scene with a painting of the 일월오봉도 Irworobongdo behind the throne. The paint on the interior of the Myeongjeongjeon is pretty faded though.

A three dimensional image at the center of the ceiling above the throne depicts a pair of phoenixes.

The courtyard containing the Myeongjeongjeon is large, though about the same size as the one prior.

We walked through a small gate between buildings to end up at a small courtyard just to the south of the Myeongjeongjeon. A sign describes this space:

Munjeongjeon Hall was the office where the king attended to routine affairs and held meetings with his officials. Unlike Myeongjeongjeon facing east, Munjeongjeon faces south. It was primarily used as an office but was also used to enshrine the royal spirit tablets after funerals. Munjeongjeon and its other facilities were destroyed during the Japanese occupation, and the building that we see today was rebuilt in 1986. The wall that used to stand west of Munjeongjeon (to the left) has not been restored

A rather inconveniently placed informational sign blocks the view of the interior of the Munjeongjeon. It doesn’t say anything that the sigh outside does not.

The paintwork in the Munjeongjeon looks to be much newer than in the Myeongjeongjeon. But, presumably, the Myeongjeongjeon should have the bright colors that we see here.

We continued around the Munjeongjeon, ending up behind the Myeongjeongjeon. There are some additional small buildings here.

A passageway and gate leads to an open area to the west. Looking back, we can see where we came from. A sign here describes this area:

Sungmundang and Haminjeong are buildings behind Myeongjeonjeon, the main hall. Sungmundang was rebuilt in 1830. It was used by the king to hold conferences and discussions with scholars on state affairs and classical literature and to throw banquets to encourage them. The open porch at the front served as the entrance. The building name plaque written by King Yeongjo (1724-1776) remains. Rebuilt in 1833, Haminjeong Pavilion was where the king received government officials who earned the highest scores on state civil and military examinations. Haminjeong means "the whole world is soaked with the benevolence and virtue of the king." As if symbolizing its name, this pavilion is open in all directions.

The 숭문당 Sungmundang is the building we saw from behind the Myeongjeongjeon.

This small pavilion is the 함인정 Haminjeong.

There is a hill to the west with a wall and other buildings on top. This wall separates Changgyeonggung from 창덕궁 Changdeokgung, which we already visited on this trip. More specifically, the buildings beyond make up the 낙선재 Nakseonjae, the place where the last of the Korean royal family lived.

While we were here, we heard a very angry woman screaming from beyond the wall. We weren’t sure what she was saying. It felt a bit like we were in a K-Drama!

We turned to the north, reaching the 경춘전 Gyeongchunjeon. A sign describes this building along with the 환경전 Hwangyeongjeon, which is out of view to the right:

Gyeongchunjeon was the bedchamber of the wife of the deceased king, and Hwangyeongjeon was the bedchamber of the current king. Both buildings were rebuilt in 1834. Each building originally had a separate area surrounded by cloisters (used as shelter for low-ranking palace workers or for storage). Gyeongchunjeon was also used as a delivery room, and this is where King Jeongjo and King Heonjong were born. To commemorate his own birth here, King Jeongjo wrote a name board reading Tansaengjeon, meaning "Birth Hall," and hung it above the entrance. Hwangyeongjeon is where King Jungjong and Prince Sohyeon passed away. The area behind this building to the north used to be crowded with the sleeping quarters of the wife and concubines of the deceased king, but it is empty today.

The front of the Gyeongchunjeon as seen from up close.

We were able to peek in through an open window.

Looking behind the Gyeongchunjeon, we could see a chimney, possibly for the building’s ondol.

We also went over to the Hwangyeongjeon to take a look.

The open shutters weren’t secured to anything and were flapping in the wind. We were able to peek inside but couldn’t really see much.

This structure, to the southeast of the Hwangyeongjeon, is described on Google Maps as the 오층석탑 Five Story Stone Pagoda. It was drawn, but not labelled, on the palace’s paper map. We don’t know anything about this pagoda.

We could see the Haminjeong again from here. It is now to our south, while before it was to our north.

To the north, we could see a pair of buildings as well as stairs that lead up a hill behind the buildings. A sign describes these the two buildings:

Rebuilt in 1834, Tongmyeongjeon served as the queen's residence. As an important building of living quarters, it has a wide elevated stone terrace in front. The center section of the building is a wood-floored hall and on either side is an ondol (heated floor) room. The yard to the west is a garden with a round well and square pond, and the waterway running between them was painstakingly crafted from stone. Rebuilt in 1834, Yanghwadang was the residential quarters for the queen mother, but King Injo lived here when he returned from refuge at Namhansanseong Fortress during the Manchu invasion of 1636.

The 통명전 Tongmyeongjeon, the building on the left, is the larger of the two.

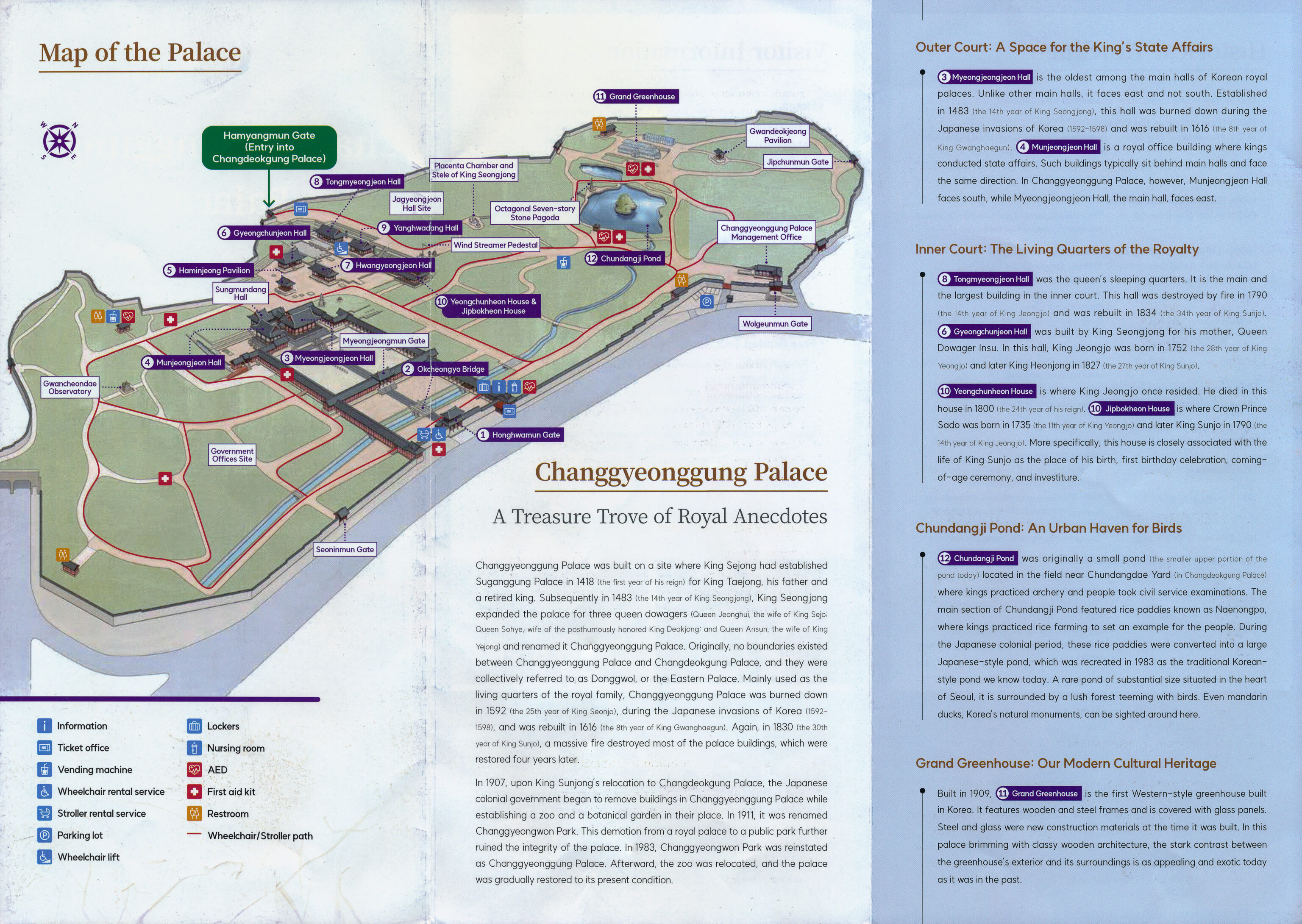

We were able to look in through an open door. We could just see an empty room. The signs inside are all written as if access is allowed, and maybe it is at certain times. But, a sign, not visible in this photograph, in front of the entrance says “Do Not Enter.”

These seem to be the stone elements of the garden area described on the sign.

The path here heads to the west and up a hill. The east entrance to Changdeokgung is at the top of the hill.

We returned to the east to quickly look into the adjacent 양화당 Yanghwadang. Again, there isn’t really anything to see inside other than an empty room.

The elevated view from atop the elevated foundation of the Yanghwadang gives us a nice perspective of most of the palace areas that we came from.

We continued on to the stairs leading up the hill. The bottom of the stairs is natural stone with a warning that it is slippery when wet,

After walking up a bit, we looked back and saw the N Seoul Tower in the distance above Namsan.

We missed this building to the east of the stairs. We’ll have to try and visit it later.

There were some benches atop the hill, a perfect place to rest as some were in the shade provided by the trees.

The hill provided a really good view to the south.

We could see some objects to the east. We went over to take a look. The one on the right within the fence is something like a modern-day windsock while object atop the stone pedestal to the left is a sundial. They are described on a sign:

Punggidae is a stone pedestal with a hole at its top into which a pole was inserted with a streamer used to indicate the speed and the direction of the wind. It is believed to be a relic of the 18th century. The stone pedestal is exquisitely decorated with scroll designs. Angbuilgu, the Hemispherical Sundial we see here, is a reproduction of one produced in the late 17th century, designated as a treasure.

There is another sign that has a more detailed description of this sundial:

Angbuilgu, the Hemispherical Sundial was one of the most widely used astronomical scientific devices during the Joseon dynasty. Its name was originated from its pot shaped feature facing the sky. It was invented in 1434, the 16th year of King Sejong's reign. There is a gnomon pointing towards the north as well as 7 vertical lines and 13 horizontal lines which indicate time and 24 seasonal divisions of the year respectively. The innermost and outermost line indicate summer solstice and winter solstice respectively.

A third sign further describes the sundial:

The shadow of the needle(called Yeongchim) on the Hemispherical Sundial indicates the true solar time. Since the standard time we use today is based on the mean solar time at longitude 135 degrees east, a time correction table should be used to adjust the equation of time, or the difference between the mean solar time and the true solar time. The method is to add the difference to the true solar time.

This seems to be just a stone sculpture?

We followed this path to the north.

This stone marker and adjacent stone structure, a Taesil, were for the storage of royal placentas and umbilical cords. The ceremony where this is performed is a Taejang. An adjacent sign reads:

Taesil is a placenta chamber of varying sizes where the royal family stored the placenta and umbilical cords of their children. Taesilbi is a stone monument inscribed with a story about the placenta. Taesil is found at auspicious locations throughout the country. The taesil of King Seongjong was originally built in Gwangju, Gyeonggi-do Province. Around 1928, during the Japanese Colonial Period, the Japanese moved most taesil of the royal family of Joseon to Seosamneug Tomb in Goyang-si, Gyeonggi-do. They moved the Taesil of King Seongjong here for research because it was the best preserved of all royal Taesil.

We continued on from the Taesil. A sign at the bottom of this curved path describes this wooded area:

The woods we see in front were a residential area for ladies of the royal family and their maids. Yohwadang and Chwiyoheon were buildings King Hyojong built for his daughters. Tonghwajeon was used to enshrine royal tablets after funerals. Between these buildings were many small houses for court ladies, and those with history relating to young princes. A great fire in 1830 destroyed many of these buildings, and the rest were dismantled during the Japanese occupation.

Continuing on through the forest, we reached a pond. A sign describes this pond, the 춘당지 Chundangji:

Chungdangji Pond actually consists of two separate ponds. The original Chundangji, a smaller pond, is above and behind the larger pond seen from this point, which was made by combining eleven rice paddies on royal farmland, called Naenongpo, in 1909. On this farm were rice paddies and a mulberry field where the king and queen experienced farming and raising silkworms for themselves. The island on the larger pond was created in 1984.

We continued to the north via the west side of the combined pond.

We passed by what seems like a maple with red leaves.

A little rest area was nearby.

We came upon the 팔각칠층석탑 Octagonal Seven-Story Stone Pagoda. In addition to having a description on the National Heritage Department website along with audio in English and Korean, there was a sign describing it here:

The three-tier base of the stone pagoda consists of (from the bottom) a rectangular platform, a two-level octagonal platform, and an octagonal lotus pedestal with lotus patterns on each side. The body of the pagoda resembles an octagonal seven-story building, particularly with its first level composed of a lotus pedestal, long rotund body, and capstone. The finial features a tiled roof-shaped roof stone placed beneath a white bead-shaped stone. There is an inscription on the body of the first level, where the phrase "the 6th Seonghwa year" indicates that the pagoda was built in 1470.

There are fish in the pond. We also saw what seems like a Gray Heron on the opposite shore. It is in this photo but appears rather small due to the distance as well as slightly wide view.

We continued on north of the pond and passed by what seems like a small garden area to the east.

Ahead, we could see a modern looking greenhouse building. We decided to look around a bit before going closer to check it out.

We could see a small pavilion through the trees. A nearby sign describes this area, the northernmost section of the palace:

Gwandeokjeong was built in 1642 as a pavilion for archers. The surrounding area was used as a military training site and for state military examinations. Behind the pavilion was a thick forest of many trees, whose beautiful foliage was praised in poems composed by a number of kings. Jipchunmun, up the hill, is a gate on the wall north of Gwandeokjeong, and faces the Confucian Shrine called Seonggyungwan, outside the palace.

The pavilion that we see is 관덕정 Gwandeokjeong. We decided to try and get closer to this small pavilion and followed a path through the trees to the east.

We passed by this entrance to the garden area, now to the south, that we saw earlier when it was to the east.

This was as far as we could go. It seems like it might lead to the Jipchunmun. The sign mentions to be careful of snakes. Surprisingly, there is an addition to the sign that says to watch out for wild pigs!

We made it to the Gwandeokjeong. It is a pretty simple structure.

We headed back to the west to check out the greenhouse, listed as the 대온실 Grand Greenhouse on the Korea Heritage Service’s website. It is described as Korea’s first Western-style greenhouse.

There are various plants inside, as one would expect from a greenhouse. We walked through on the northern half of the building.

It even has fish!

We went to the far western end of the building and circled back via the southern half of the building.

This little mountain scene is pretty detailed and includes a small wooden building.

We ended up exiting via a door on the south side of the greenhouse in the middle of the building. There was a fountain outside, though it was dry, much like European fountains in the winter!

While return to the south via the east side of the pond, we came across a Gray Heron. It could possibly be the one we saw before from afar. It was clearly actively hunting.

The heron strikes! Did it catch anything?

It got a tiny little fish!

We watched as the heron quickly caught another tiny fish. This one was a bit larger but still tiny.

We watched it get another tiny fish…

And, another. We’ve seen herons eat fish that are surprisingly large so these little ones are probably all it could get here. At least its success rate was 100% while we were observing!

We continued to the south, seeing the Octagonal Seven-Story Stone Pagoda to the west on the other side of the pond.

We passed by two cats, though we only got a good photo of one of them.

We continued to the south until we came out of the wooded area. We could see the top of the Honghwamun, the main entrance and exit, ahead.

The N Seoul Tower was visible as well.

But, we still had to return to the building that we missed earlier! This building was originally two separate buildings, 집복헌 Jipbokheon and 영춘헌 Yeongchunheon , but were connected when rebuilt in 1834. A sign describes this building:

This area used to be crowed with residences. Jipbokheon was living quarters for concubines. At present, Jipbokheon, to the left, is attached to Yeongchunheon like an annex. Originally the two were separate structures. It is presumed that they were connected as they are today when they were rebuilt in 1834. Prince Sado and King Sunjo were born in Jipbokheon. King Jeongjo enjoyed reading in Yeongchunheon and passed away here. To the east (right) of this building there were many small buildings assumed to have been residences of court ladies, but none remain.

These buildings are at least partially furnished inside. We were able to look in through the windows. It is unfortunate that the majority of the palace buildings that we’ve seen in Seoul are basically empty inside.

We returned to the Myeongjeongjeon’s courtyard to head to the Honghwamun to exit. We walked via the covered passageways on the edge of the courtyard to avoid the sun.

We crossed back over the stream by the Honghwamun and headed out.

Gwangjang Market

It was past 1:15pm by the time we left the palace. We decided to take a bus to 광장시장 Gwangjang Market to get a late lunch.

We walked though part of the busy market but ended up first having a snack at White Button, a dessert cafe. There was a painting of a whale in the second floor seating area.

We ordered a white peach bingsoo, something we haven’t encountered so far. The fruit was fresh and the milk snow was good too.

Back inside the market, we weren’t really sure what we wanted to try. We got a fried mung bean bing from a random place in Gwangjang Market as many vendors were selling the same product. It isn’t really any better than what we can make at home.

We decided to have knife cut noodles and mandu at Gohyang Kalguksu, one of the busiest stalls in Gwangjang Market. Gohyang Kalguksu was featured on the Seoul episode of Netflix’s Street Foods Asia. We’ve actually seen the episode before but forgot about it until rewatching it in the evening.

The knife cut noodles were well made but the broth was extremely bland.

The mandu had good flavor in the filling but many of the wrappers had fallen apart when served, which is pretty terrible. Overall, we felt this stall wasn’t really anything particularly special. Definitely a hard pass. Interestingly, we found that most of the vendors in the market basically were selling the same product. There were likely minor variations but it was just stall after stall after stall of the same thing. Quite different from, say, the hawker centers in Singapore where there is a huge variety of good and cheap food.

The market is on the north side of the 청계천 Cheonggyecheon. We crossed a bridge over the river to take a look east and west before continuing on.

Jongmyo

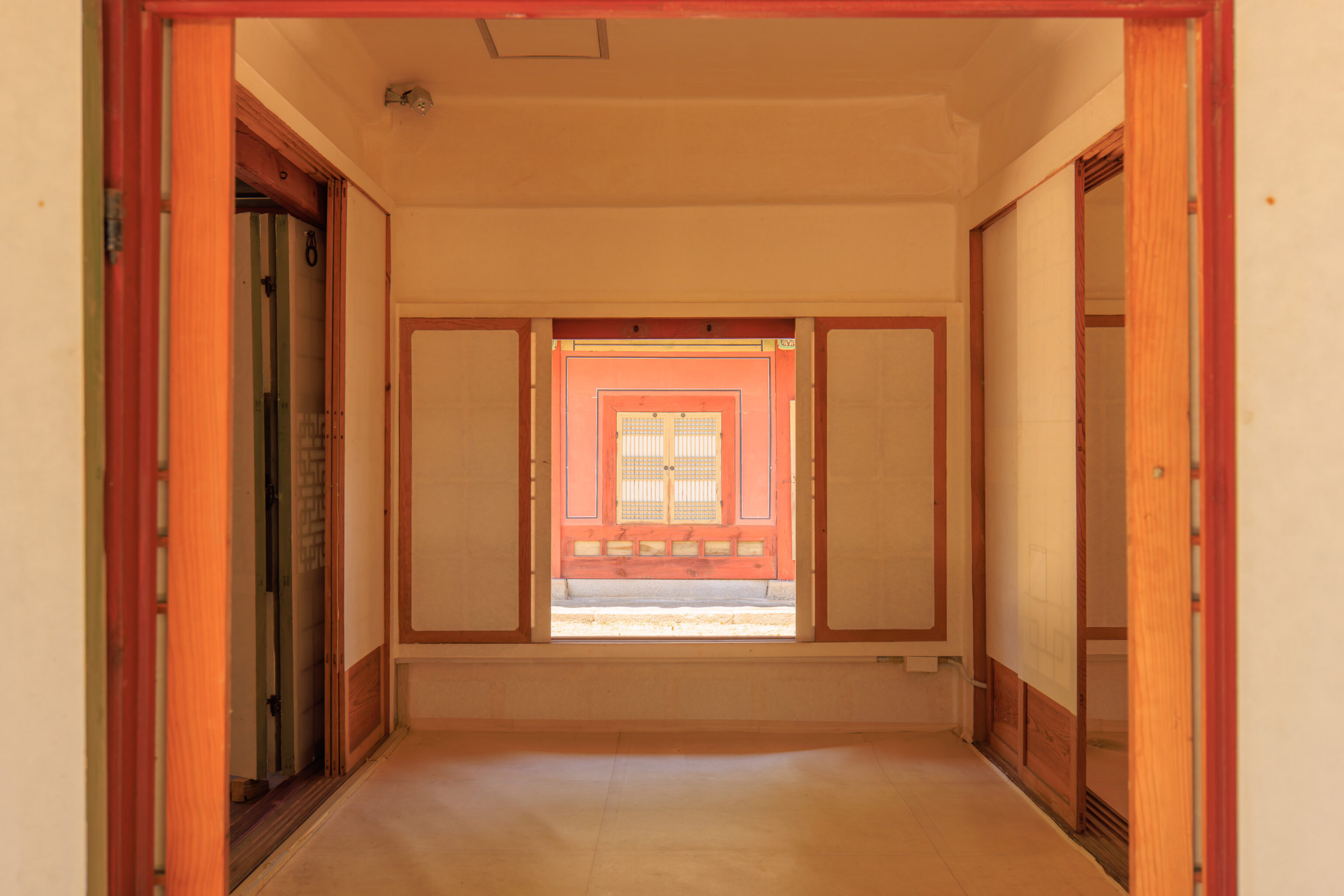

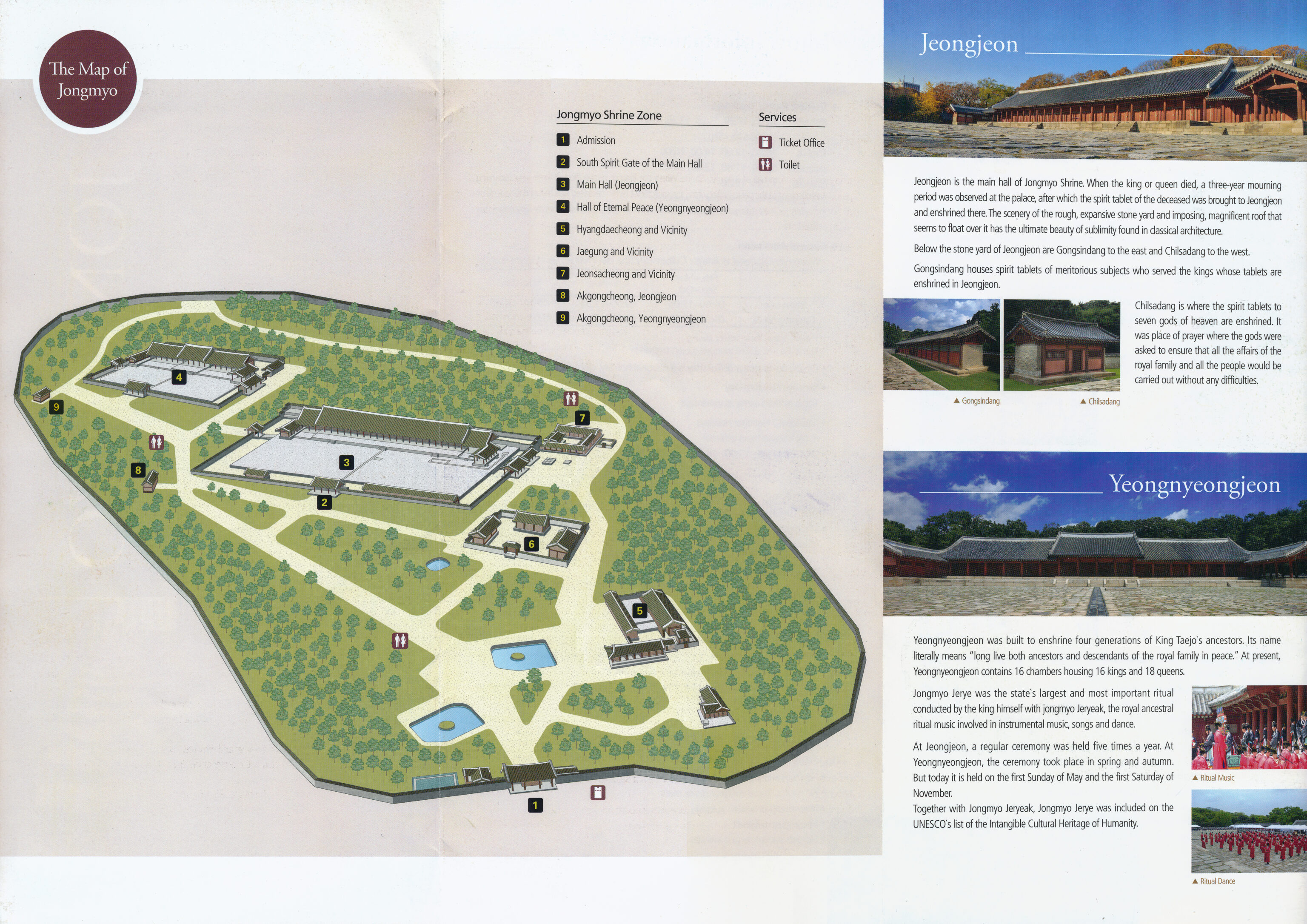

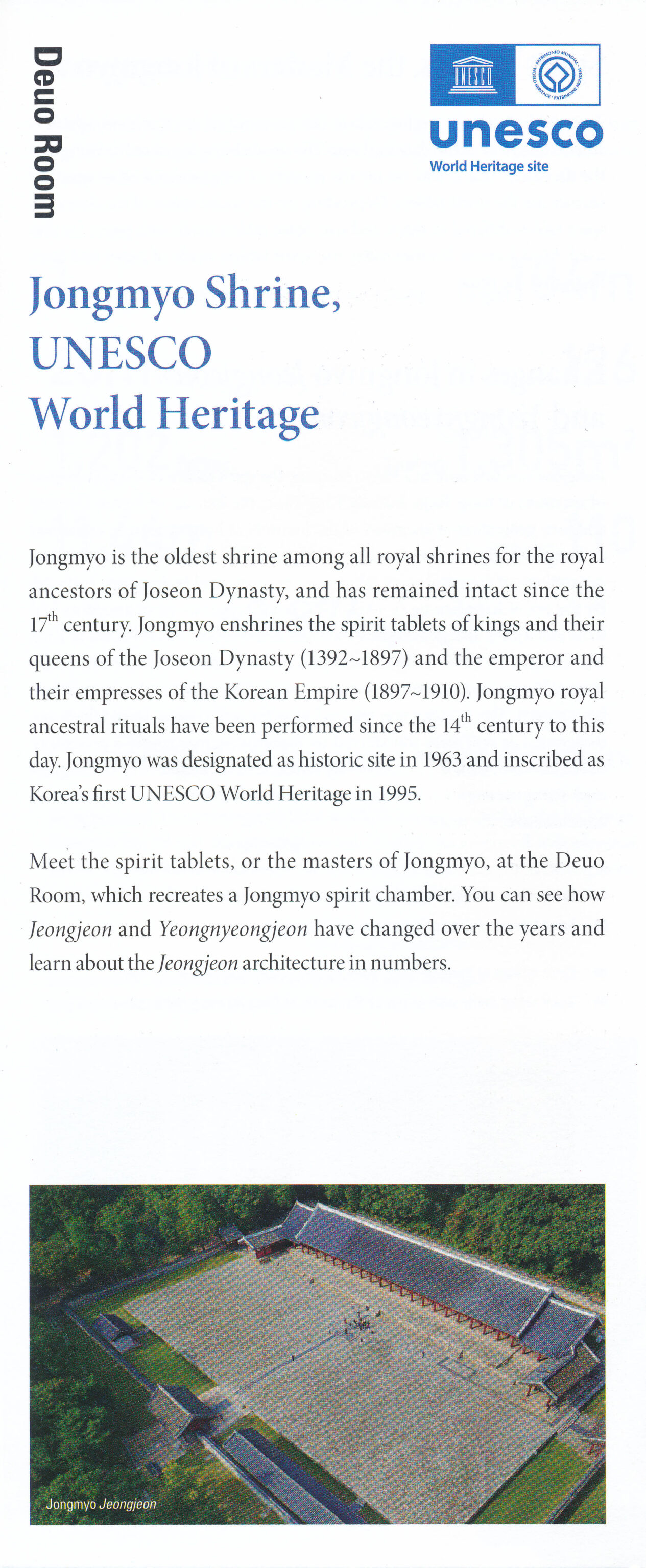

We headed to 종묘 Jongmyo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, next. Jongmyo is a shrine dedicated to the Joseon dynasty royal family and is within walking distance to the west of Gwangjang Market.

The entrance to Jongmyo is on the southern edge of the shrine’s grounds. It goes through a small park area with some historical artifacts on display. A sign describes the covered well visible here:

Jongmyo Eojeong (Royal Well)

Designation Number: Tangible Cultural Heritage of Seoul No. 56 Period: Early Joseon Period

Location: 2, Hunjeong-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul

Located near Oedaemun Gate, the main entrance to the Jongmyo Shrine, this water well is called Jongmyo Eojeong, or the Royal Well of the Royal Ancestral Shrine, largely because Joseon kings would drink from it whenever they visited the shrine for state events. The well has a diameter of 1.5 meters and a depth of 8 meters.

A concrete pipe was installed inside the well in the early 20th century when Korea was under the Japanese colonial rule so that it could continue to supply drinking water. The well was designated as Seoul Tangible Cultural Heritage No. 56 in November 1983.

The well is no longer used as a source of drinking water, but historical records say that it never failed to provide fresh drinking water as cool as ice during summer and warm in winter, even during the driest season. Due to the fame of the well, the name of the district in which it is located was changed to Hunjeong-dong or 'Steaming Well District'.

Another item that was on display.

We walked to the north until we reached the entrance into Jongmyo.

We picked up an informational pamphlet and map. There was also a sign on the other side of the gate. It provided a lengthy description of Jongmyo in one paragraph:

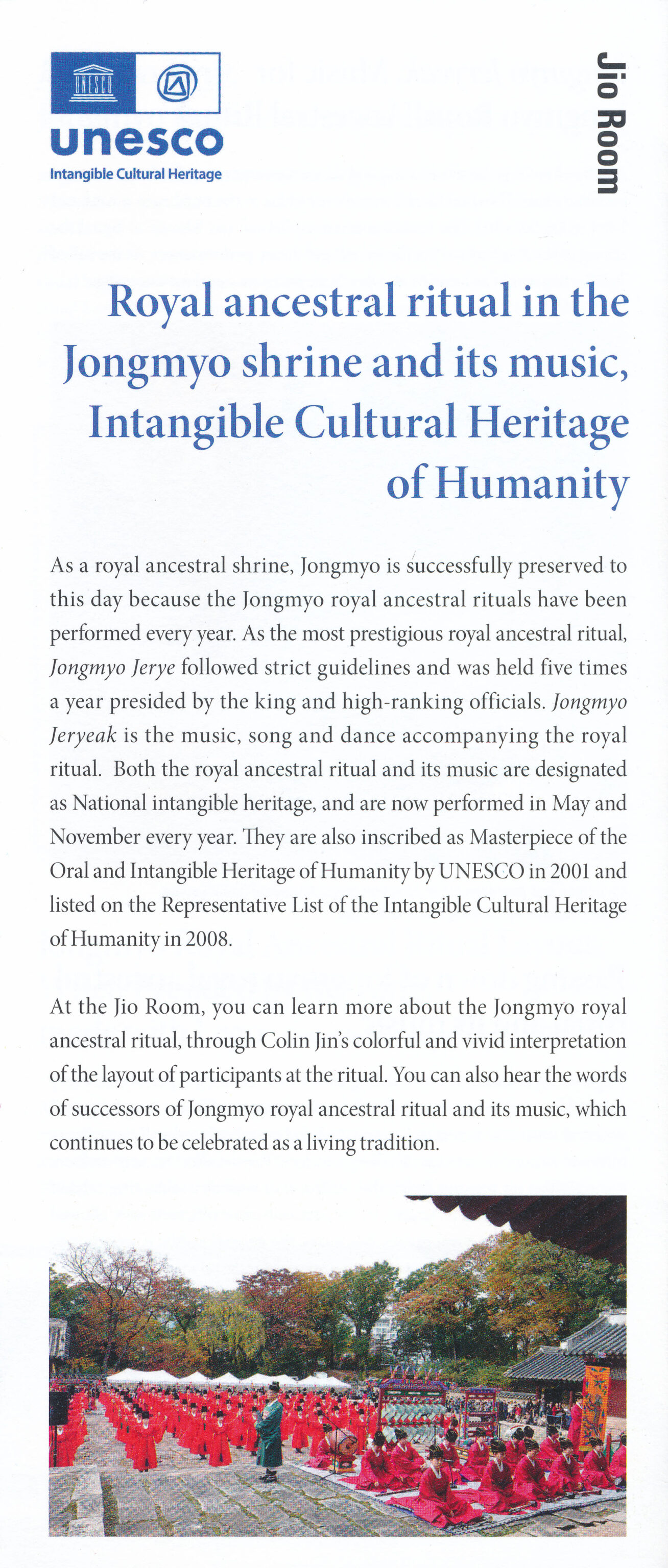

Jongmyo Shrine is the supreme shrine of the state where the tablets of royal ancestors are enshrined and memorial services are performed for deceased kings and queens. King Taejo, founder of the Joseon Dynasty, started construction of Jongmyo Shrine as soon as he designated Hanyang (today's Seoul) as capital of the newly founded dynasty. The construction of Jongmyo was completed in 1395, before that of Gyeongbokgung, the main palace. According to Confucian philosophy and the concepts of geomancy, Jongmyo, the national shrine, was built on the east side of the royal palace, to its left, and Sajik Shrine, where ritual services for the gods of earth and crops were performed, was built on the west side of the royal palace, to its right. As more and more kings and queens were enshrined with the passage of time, the facilities were necessarily expanded to what we see today. When a king or a queen died, mourning at the palace would continue for three years after the death. After the three-year mourning period was over, memorial tablets of the deceased were moved to Jongmyo and enshrined. Kings credited with outstanding, virtuous deeds are enshrined in Jeongjeon, the main hall. In Yeongnyeongjeon are the tablets of King Taejo's ancestors of the preceding four generations and those who were posthumously crowned as king. There are also tablets that were moved from Jeongjeon. At present, Jeongjeon has 19 spirit chambers and houses a total of 49 tablets. At Yeongnyeongjeon, there are 16 spirit chambers and 34 tablets. The tablets of two kings, Yeonsangun and Gwanghaegun, who were deposed from the throne, are not kept in Jongmyo. Jongmyo Jerye, the Royal Ancestral Rite, was the most important state ritual. It was conducted five times annually at Jeongjeon and twice annually at Yeongnyeongjeon. The king performed the ritual himself. The crown prince and all high-ranking civilian and military government officials attended Jongmyo Jerye. Royal ancestral ritual music involved instrumental music, singing, and dancing. At present, Jongmyo Jerye is performed once a year, on the first Sunday of May. Other ceremonies to report important state affairs or to pray for the state are also performed at Jongmyo. None of Jongmyo's facilities are lavishly adorned; they emphasize only solemnity, piety, and sublimity. In its extreme simplicity, we can feel the deep meaning of life and death, and in its stately serenity, we feel the sacred authority of the Joseon Dynasty. Of all Confucian states in Asia where counterparts to Jongmyo Shrine were established, Korea is the only one that has preserved its royal shrine and continues to conduct royal ancestral rites, known in Korea as Jongmyo Jerye and Jongmyo Jeryeak. This is the main reason that Jongmyo Shrine was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1995 and Jongmyo Jerye and Jongmyo Jeryeak were inscribed on the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2001.

A sign on the path beyond the gate notes that it is for spirits only.

We ended up walking through the shrine counter-clockwise. We passed by a pond on our left.

The first building we saw was the 망묘루 Mangmyoru. This was in use as a sort of activity space for kids but historically, it was used as a resting place for the king. A nearby sign describes the two buildings in this area.

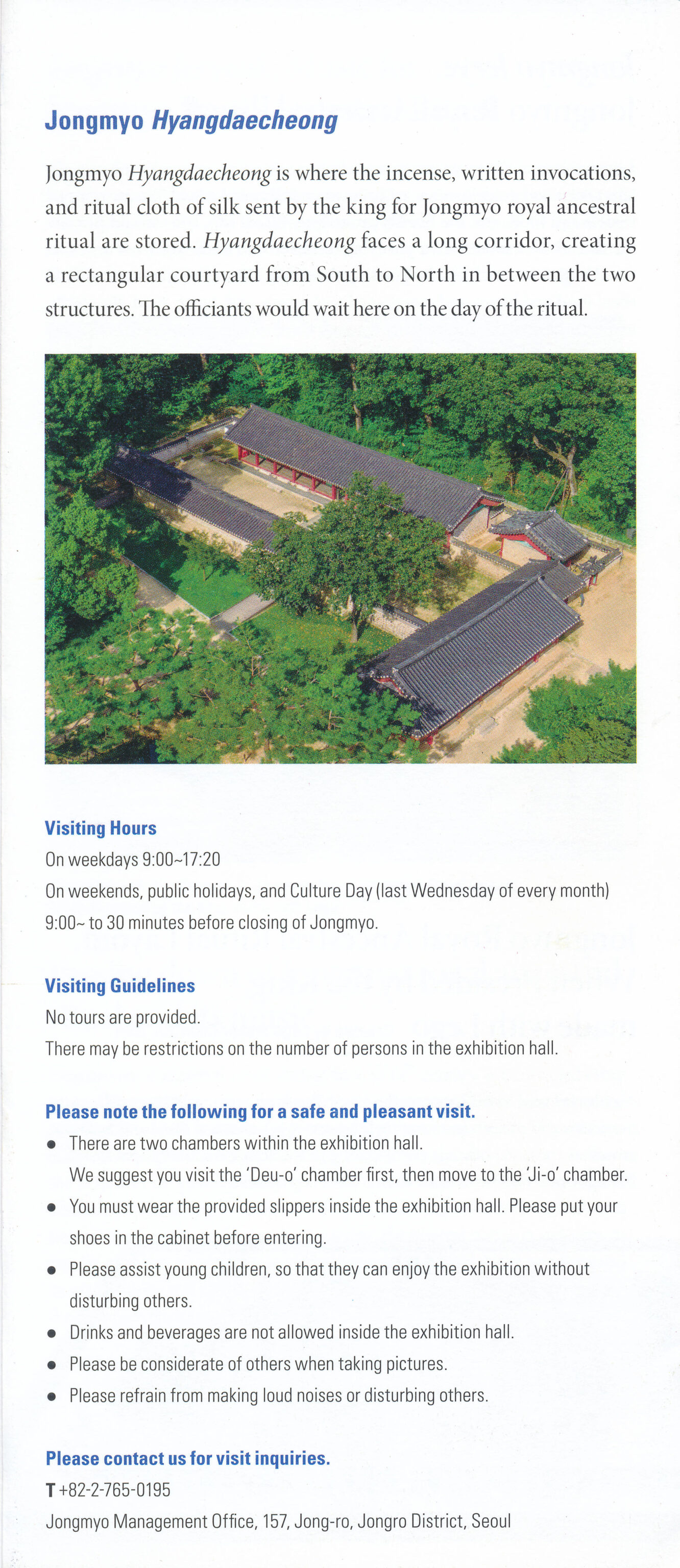

Hyangdaecheong is a storage room for ritual supplies, where incense, ritual paper, and offerings were kept and officiants who would minister at ancestral rituals stood by. Jipsacheong, a government office of rituals, was also part of Hyangdaecheong. Mangmyoru Pavilion to the south is where the king would take short rests when visiting to pay tribute to deceased kings and conduct rituals. In front of Mangmyoru is a pond, jungyeonji, and behind Mangmyoru is a shrine housing a portrait and scrolls of King Gongmin.

Part of the Mangmyoru seems to currently be in use as an office, as described on another sign:

Mangmyoru is the office space used by officials of Jongmyoseo, a government agency in charge of overall management of Jongmyo. Jongmyoseo oversaw ritual food used at Jongmyo royal ancestral ritual as well as the maintenance and repair of buildings on Jongmyo grounds. There is a piloti-like structure on one end of Mangmyoru. It is where the king would wait thinking of his ancestors until Jongmyo royal ancestral ritual begins. Let's listen to the words of those who take care of Jongmyo from past to present. We hope you will remember Jongmyo with the view of Jeongjeon and Yeongnyeongjeon from Mangmyoru.

This small space is described as a shrine to King Gongmin and his wife, a Mongolian princess:

This is a shrine honoring King Gongmin, the 31st monarch of the Goryeo Dynasty, and his wife Nogukdaejang Gongju, a princess from Mongolia. King Gongmin restored the sovereignty and territory of Goryeo by defeating Yuan China and implemented sweeping reforms. He was also a talented artist. A horse painting which is said to have been made by King Gongmin himself is kept inside the shrine. It is extraordinary that a king of Goryeo should be enshrined in Jongmyo Shrine, the supreme shrine of the Joseon Dynasty. The exact reason for this is not known,

We continued on to the Hyangdaecheong. The building is actually though the gate on the right.

We picked up a pamphlet that describes the contents of the Hyangdaecheong.

Text on the wall describes the layout of the spirit chambers within the shrine’s two main buildings, 정전 Jeongjeon and 영녕전 Yeongnyeongjeon:

Jongmyo's Jeongjeon and Yeongnyeongjeon each have multiple chambers within its building that enshrine spirit tablets. Jeongjeon enshrined 49 spirit tablets in 19 chambers and Yeongnyeongjeon enshrines 34 spirit tablets in 16 chambers.

All spirit chambers are identical in their layout. Against the back wall of the chamber, a spirit tablet cabinet is placed at the center, with a cabinet for investiture books to the west and a cabinet for royal seals to the east. In front of the spirit tablet cabinet stands the spirit altar with holders for the spirit tablets on top. The ritual tables are placed in front of the altar. On the floor just beneath the ritual tables, there is a small hole. This hole is where the ritual liquor is poured into at the beginning of a ritual. The poured liquor reaches the soil beneath to summon the spirits of the body of the deceased to the rites. At the entrance of the spirit chambers, royal parasol and fan were placed, symbolizing dignity of the king and his queen. The spirit chambers are built to serve a ritual function to honor the dynasty's dignity.

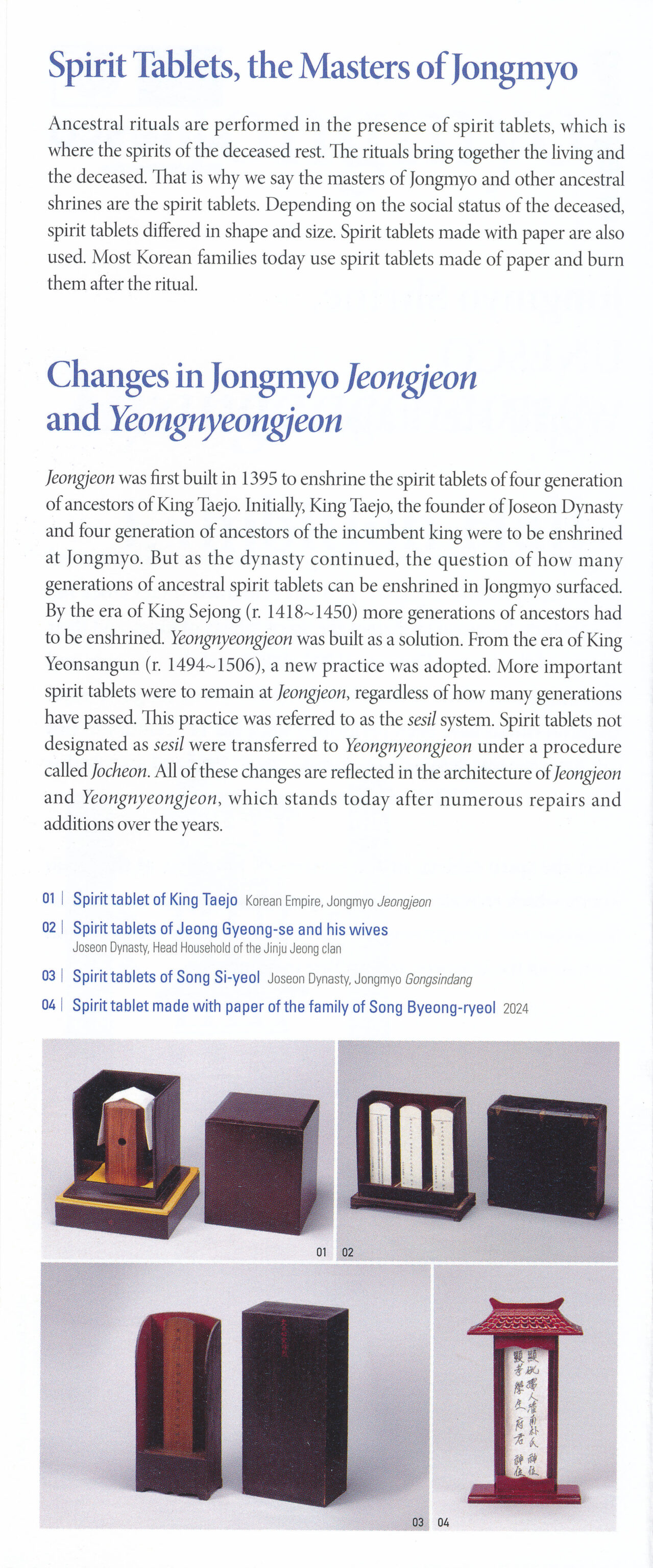

This room seems to be what is being described? Additional text describes sprit tablets:

Spirit tablet is a symbolic place where the spirit of the deceased rests. By performing ancestral rituals in the presence of spirit tablets, the living can once again meet with the deceased. In Korea, performing ancestral rituals with spirit tablets of one's ancestors were common practice not only for the royal courts but for the noblemen and ordinary people alike. Spirit tablets were made in different shapes, depending on the social status of the deceased, but always used chestnut wood. Modern Korean families use spirit tablets made of paper. Take a look at the different spirit tablets of kings, meritorious officials of the court, noblemen and ordinary families of modern times.

Further text describes the ritual performed to honor the spirts of the deceased royalty:

Jongmyo Jerye is the ancestral rituals performed to honor the late kings and their queens, emperors and their empresses enshrined at Jongmyo. The king demonstrated his legitimacy to the throne by presiding over Jongmyo royal ancestral rituals and prayed for the everlasting prosperity of the dynasty.

Joseon dynasty's Jongmyo royal ancestral ritual began when King Taejo (r. 1392-1398) founded the dynasty. It was the most prestigious, large-scale rite among all state rituals. It was held five times a year. Cow, sheep and pig were offered as sacrifice and their meat were key elements of the ritual food, along with newly har- vested grains such as rice and millet and other items collected from land and sea. Ritual officiants performing Jongmyo ancestral ritual purify both their body and mind before the rites. They go through a careful process of examining and preparing the sacrificial animals and have everything ready to begin the rituals at 1 am on the day of the rite. Jongmyo ancestral ritual follows the steps of greeting the spirits, offering them ritual food and liquor, receiving the blessings of the spirits by sharing the ritual food and finally sending the spirits off. Each step is accompanied by music, song and dance performances.

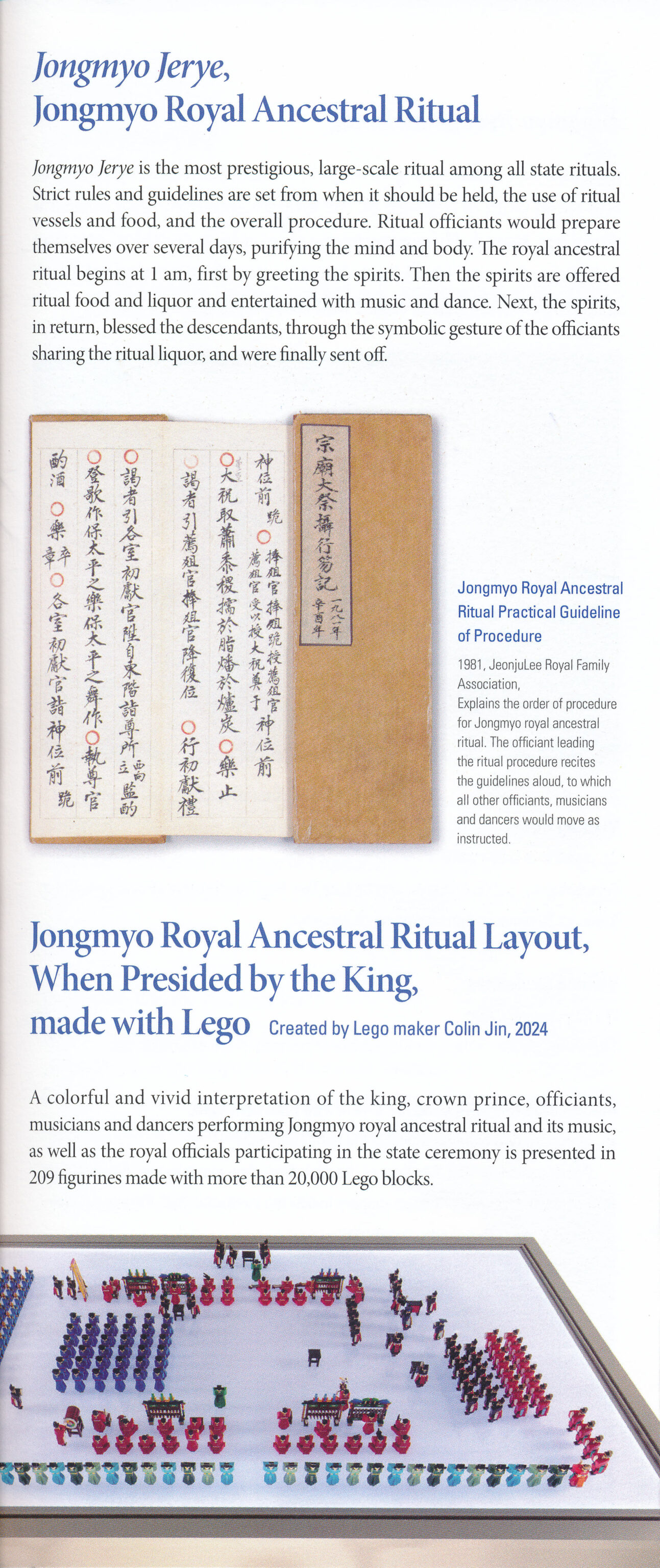

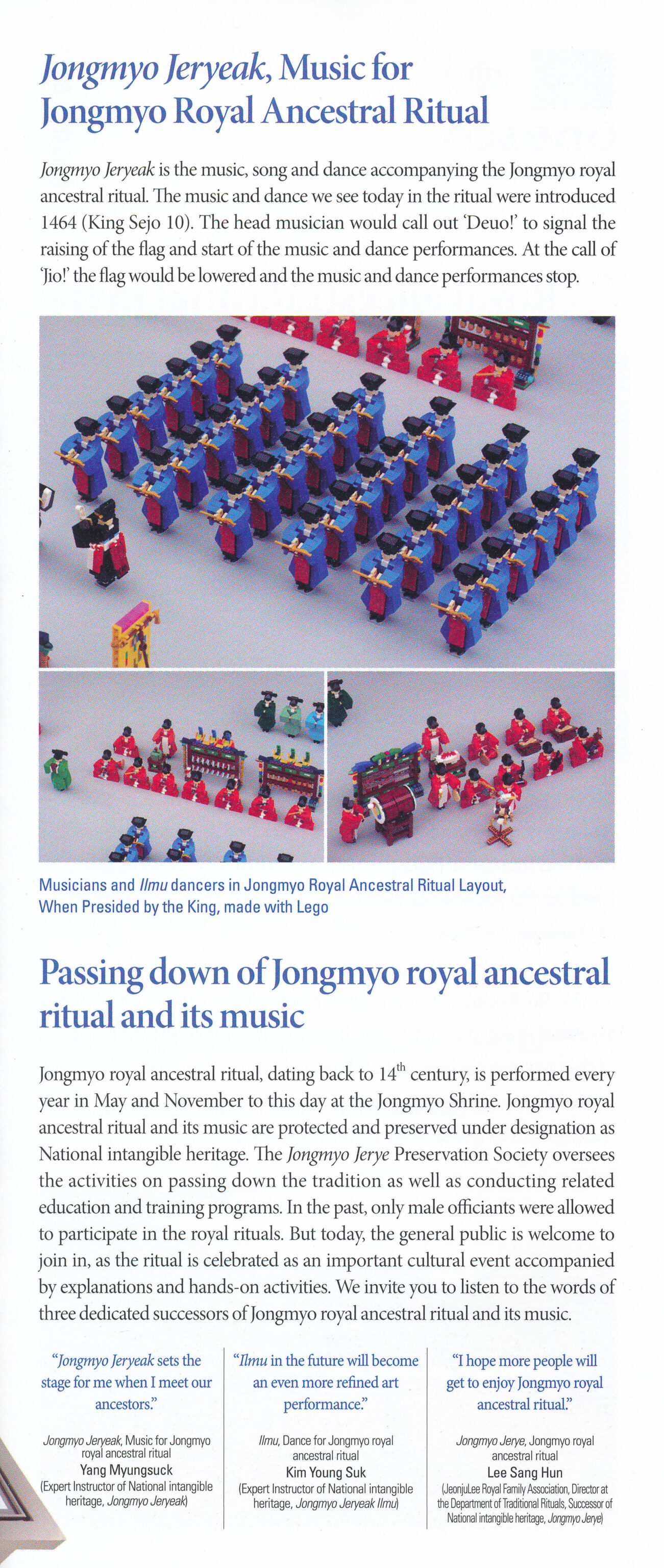

These Legos depict what the Jongmyo Jerye would have looked like. Text on the wall describes this display:

Lego maker Colin Jin has created the full layout of officiants, musicians and dancers performing Jongmyo royal ancestral ritual and its music, as well as the royal officials participating in the state ceremony using Lego blocks. More than 20,000 blocks were used to masterfully create 26 different types of musical instruments, and over 209 Lego figurines.

Colin Jin has been making fun toys with Lego for his child and this fueled his creative Lego designs. He has created reinterpretations of Korea's national heritage in hopes that his works can embody the human history and its evolution in the most natural and Korean way.

It seems it is possible to observe the ritual being performed in modern times, as described in additional text:

Jongmyo Jerye, Jongmyo royal ancestral ritual continued for over 500 years until the fall of the Joseon Dynasty. It was briefly interrupted from 1945 but resumed in 1969. In 1975, Jongmyo Jerye was designated as National Intangible Heritage. In 1986, the Jongmyo Jerye Preservation Society was recognized as the official institution in charge of the passing down of Jongmyo royal ancestral ritual. Today, Jongmyo royal ancestral ritual is performed twice a year; on the first Sunday of May and the first Saturday of November. Special lectures are given every week to pass down the tradition of Jongmyo royal ancestral ritual.

Jongmyo no longer needs to provide legitimacy of a dynasty. However, Jongmyo royal ancestral ritual rep- resents our way of expressing gratitude and exercising filial duties to our ancestors, which are core values that still lives on. The current practice of Jongmyo royal ancestral ritual has adopted a few changes for the convenience of both its performers and the public audience. Instead of performing the ritual five times a year, it is now held twice a year in spring and autumn. The hour of the ritual has moved from 1 am to daytime. The ritual officiants served by royal court officials in Joseon Dynasty are now served by descendants of the royal family and families of queens. Jongmyo royal ancestral ritual is now open to the general public, celebrated as an important cultural event accompanied by explanations of the event and hands-on activities to enjoy.

We missed it by about a month!

There is quite a bit of text and other informational displays within the Hyangdaecheong. We exited the building after awhile and continued on our way.

The next cluster of buildings, within a small courtyard by the southeastern corner of the Jeongjeon, is where the king and crown prince prepared to perform rituals. It is described by a sign:

Jaegung is where the king and the crown prince made their preparations for ancestral rituals. It is also called Eojaesil or Eosuksil. Eojaesil, where the king stayed, is to the north. Sejajaesil, a room for the crown prince, is to the east. Eomokyokcheong, a bath facility is to the west. The king and the crown prince entered through the main gate of Jaegung and stayed here to purify their minds and bodies, exited by the west gate, and then entered Jeongjeon, the main hall, through the east gate to perform the rituals.

The Jeongjeon, which is being renovated, was visible from here.

We continued down a tree-lined path to the east of the Jeongjeon.

We passed by a closed gate to the Jeongjeon.

The Jeongjeon, under a protective shell for the renovations, is visible in the background.

The next area we reached, at the northeast corner of the Jeongjeon, contains kitchens used to prepare food used for the rituals.

Jeonsacheong is a kitchen where foods were prepared for rituals. In ordinary times, ritual vessels and tools were kept inside this rectangular-shaped building. On the courtyard, stone mortars used for preparing food remain. Subokbang, between Jeonsacheong and the east gate of Jeongjeon, was the quarters used by officials guarding Jongmyo Shrine. In front of Subokbang are raised areas named Chanmakdan and Seongsaengwi. Chanmakdan is where the food was given a last check before being taken out for rituals. Seongsaengwi is where animals such as cows, sheep and pigs were examined before being sacrificed. To the east of Jeonsacheong is Jejeong, a well used for rituals.

제정 Jejeong, the well used for the rituals, is here.

We followed the path as it went to the north and then west until reaching the northwest corner of the shrine grounds. It then headed down south.

Soon, we could see the Yeongnyeongjeon on our left. We entered via the gate ahead, on the west side of the building. A sign describes the Yeongnyeongjeon:

Yeongnyeongjeon (Hall of Eternal Peace) is an annex to the main hall, Jeongjeon, It was built in 1421 when Jeongjeon could no longer accommodate any more spirit tablets, The name Yeongnyeong means "may the ancestors and descendants of the royal family live long in peace," The facilities and layout of Yeongnyeongjeon are similar to those of Jeongjeon, but the building is smaller and more intimate, Like Jeongjeon, it has a two-tiered elevated stone platform in front, The whole area is enclosed with walls, and three gates were built in the east, south, and west, Yeongnyeongjeon had six spirit chambers when it was first built but was eventually expanded to 16 spirit chambers as we see it today. Under the central raised section are four spirit chambers for ancestors of the preceding four generations of King Taejo, founder of the Joseon Dynasty. A storage room for ritual implements was built to the east, and Akgongcheong (Hall of Musicians) was built outside the southwest wall,

*Spirit chamber: A room for spirit tablets

*Spirit tablet: A wooden tablet inscribed with the name of the deceased

Presumably, each of the closed doors leads to a sprit chamber.

We exited Yeongnyeongjeon’s courtyard via this gate on its southern side.

The gate, and Yeongnyeongjeon behind it, as seen from the outside.

We continued following the path as it lead to the southeast. Looking back, we could see the wall around the Yeongnyeongjeon and its roof.

The 악공청 Akgongcheong, described previously at the Yeongnyeongjeon as a hall for musicians, today serves as a pavilion for visitors to rest. A sign describes this building:

Akgongcheong Pavilion of the Main Hall served as the waiting room for instrumental players and dancers during ceremonies held at the main hall. It is a modestly sized building with 6 kan in the front and 2 kan at the side.

We continued along the path as it traveled past the south side of the Jeongjeon. A nearby sign said that the renovations started on June 22, 2020 and were expected to go on until April 21st, 2025.

It was actually possible to enter the outer wall around Jeongjeon and see the shell around the building from afar.

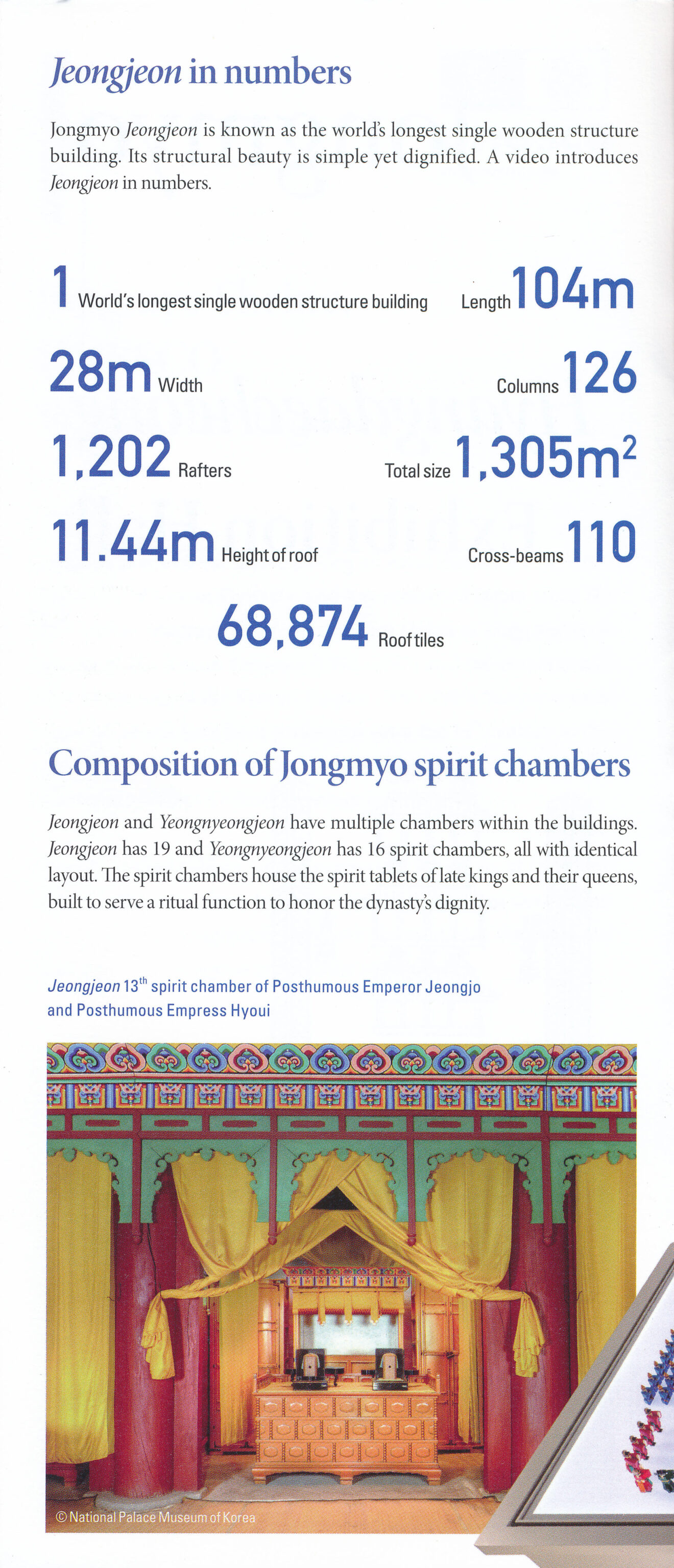

This model shows what the building looks like. A nearby sign describes the Jeongjeon :

Jeongjeon is the main hall and most important part of Jongmyo Shrine, In front of this long building stretches a massive elevated stone platform enclosed by walls on all sides, Spirits were believed to enter through the south gate in front of this sign and the king and ritual officiants entered through the east gate, Musicians and dancers entered through the west gate, When Jeongjeon was first built in 1395, it had seven spirit chambers, Additions and alterations were made over the years until there were 19 spirit chambers, making Jeongjeon a very long wooden building. The rough, expansive stone yard and imposing, magnificent roof casting its shadow over it shows the sublime beauty of classical architecture, Inside the southern walls were Gongsindang (Hall of Meritorious Officials) to the east and Chilsadang Shrine (Hall of the Seven Deities) to the west, Outside the west wall was Akgongcheong (Hall of Musicians).

*Spirit chamber: A room for spirit tablets *Spirit tablet: A wooden tablet inscribed with the name of the deceased

This sign shows what the Jongmyo Jerye looks like when performed in modern times. It also shows what seems to be the inside of the spirit chambers.

We returned to the path we were on and continued to the southeast. We returned to the pond we saw on our way in, but on the opposite side.

There is another pond right by the entrance gate. It was pretty quiet here as it was kind of off to the side. We saw a duck, probably a Mallard, resting by the water. It seemed very unafraid of people.

We exited the same way we entered. This seems to be the only way in and out.

We passed by a small Haetae.

There is a bridge over a bit of water at the southern end of the park that is outside the shirne.

These look like stairs leading to nowhere but it is actually a pedestal for a sundial. The sign to the right describes this stone pedestal:

Angbuilgu (Hemispherical Sundial) Pedestal

Angbuilgu refers to a type of sundial made in the period of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). Angbu literally means "cast iron pot that looks up into the sky" in Korean.

Angbuilgu was installed near the entrance of Jongmyo Shrine in 1434 during the 16th year of the reign of Sejong. During the Imjinwaeran, the Japanese Invasions of Korea of 1592, the main body went missing and only the pedestal remained. The sundial pedestal was often called "Iryeongdae".

When streetcar tracks were built in 1898 during the 2nd year of Gwangmu, the pedestal was buried below ground. In 1930, it was excavated and moved to Tangol Park. With the rearrangement of Jongmyo Plaza in 2015, it was relocated here based on historical research.

This stone tablet is a marker instructing riders to dismount from their horse. A bit like modern times, except usually these days it would say to dismount from your bicycle! A sign provides more detail:

Hamabi (Jongmyo Dismount Marker)

Hamabi is one of many such stones set up around the entrances to the important state institutions of Joseon, including the royal ancestral shrine and royal palaces, commanding visitors or passersby to show respect by dismounting from their horses. The first such markers were wooden signs posted at the entrances to the royal ancestral shrine (Jongmyo) and royal palaces in 1413. However, these were replaced by stone markers in 1663 when Jongmyojeongyo Bridge, which leads to the royal ancestral shrine, was renovated.

The name of the markers originated from the text engraved on the front surface: "All officials, whatever their rank, are required to dismount from their horse (大小人員皆下馬).” Gradually, dismount markers were set up in other places, including the Munmyo Confucian Shrine and the birthplaces of great sages and scholar-statesmen.

We noticed that there was a system to mist the street at the shrine’s bus stop. Not something we’ve seen before. A YouTube video mentions that this is to provide a cooling effect for the road during hot summer days as well as to prevent the spread of Yellow Dust as it can be a problem in the region.

Hongdae

We took the bus from Jongmyo back to Hongdae but decided to get off at a stop to the north of the area near the subway station. This area was pretty different from the area near the station and had many small restaurants and cafes in narrow lanes that seemed to wind about arbitrarily.

We visited 호안끼엠 Hoan Kiem, a Vietnamese cafe, to get some bingsoo.

We noticed their air conditioner had sun protection!

We ordered a fresh strawberry bingsoo as strawberry is currently in season. It was excellent with good strawberries as well as some unknown ingredients inside. One was a tiny bit of minty sauce and there was also some fruit syrup at the bottom, possibly pineapple based.

We wandered around for awhile, eventually reaching the 경의선숲길공원 Gyeongui Line Forest Park. Here, we came across an unexpected find. There is a jiggly cat jelly which has become something of a social media sensation. It is made by 미크플로 Milkflo which has a cafe in the Hongdae LINE Friends store, or at least, in the same building. But, we came across Milkflo, the cafe that makes, it here!

We ordered the cat and a kaymak set. Kaymak, this cafe’s specialty, is actually from Central Asia, going as far west to Turkey and the Balkans, according to Wikipedia at least. The kaymak sets all come with bread and some sort of sauce. Both honey and mango were provided so we aren’t actually sure what goes with what. The kaymak itself seems to be best described as unsalted cream cheese. Definitely an interesting and different dessert from what we’re used to!

The menu on their website shows the kaymak as either a blob, like what we got, or a nicely folded thick sheet, which is what we think we were trying to get.

The jiggly cat, 미크냥이 우유푸딩 Miknyangi Milk Pudding on the menu, tasted decent, particularly after pouring on some of the provided mango based syrup.

We walked to the east along the Gyeongui Line Forest Park, a former railway that has been turned into a linear park. We reached the subway station and came across this sculpture which looks like a Joby Gorillapod. Which would be an excellent product if the legs didn’t pop off. I had one, it happened to me, luckily, I caught my camera before it fell!

We continued walking a little further to the east until we reached the Hongdae Red Road. Here, we came across an inflatable mascot for the road.

Other than the normal busking, there was what seemed to be a book fair taking place near the subway staiton.

We decided to try 홍익숯불갈비소금구이, a busy galbi restaurant that we walked by. We got beef brisket and beef galbi. The brisket was unfortunately rather tough. The galbi was fine though. A bit disappointing, we should have tried to look it up before visiting. At least we were full after the meal though!

One Reply to “Changgyeonggung and Jongmyo”