After breakfast at the Le Méridien in Munich, we took the train to Salzburg, Austria. Once there, we visited the Hohensalzburg Fortress on a hill above the city. We also visited Mozart’s birthplace and his residence, both of which are currently museums.

Morning

After waking up at the Le Méridien, we went downstairs for breakfast. It was mostly the same as was served on previous days, though the guy who works the omelette station on weekends isn’t nearly as talented as the guy who was working on the weekdays.

We then walked across the street to the Hauptbahnhof to catch the RE5, a regional service operated by the Bayerische Regiobahn. The trip to Salzburg takes a bit less than two hours and does not require changing trains. A nice bonus is that it is included in the Deutschlandticket, the €49 a month ticket that allows riding on nearly all local and regional transit options in Germany for no additional cost. This countrywide ticket is available from multiple sources, many of which don’t allow foreigners to buy it. However, we were able to get it on this trip, as well as previous trips, from the RMV, the regional transport company for the Frankfurt area. It can be purchased and used via their RMVgo app. We had no issue passing ticket inspections in various parts of Germany.

Fortress Hohensalzburg

After arriving in Salzburg, we took a bus to the Rathaus (Town Hall), on the south bank of the Salzach, a river that runs through the city. The bus was included in the Salzburg Card, a pass for tourists that includes the city’s busses as well as entrance to many of the city’s various museums, including the ones we wanted to visit. It can be purchased online and used as a QR code.

We started walking to the south to head to the funicular that runs up to the Hohensalzburg Fortress. It was pretty quiet in the area, even though it was already 10am. This seems fairly typical for the region though.

We soon got our first glimpse of the fortress up on the hill above.

This weather station is referred to as a meteorological pillar by Atlas Obscura. It has a thermometer as well as barometer.

The view looking back from the weather station.

There are many historic buildings here in the old town area of Salzburg. This historic city center is UNESCO listed.

We weren’t sure what this black banner in front of the Salzburg Cathedral represents.

We continued beyond the cathedral to reach the Kapitelplatz. This work depicting a man atop a sphere is named Sphaera. There is a second related sculpture, depicting a woman, which we unfortunately did not see.

Sphaera sits below the fortress, which occupied a huge space on the hill above the old town. From here, we could see the funicular tracks leading up to the bottom right edge of the fortress.

The fortress without the sphere.

The entrance to the funicular’s bottom station is a block to the south of the Kapitelplatz.

We caught the next funicular heading up the hill to the fortress. It is possible to walk up instead.

The funicular deposited us at the west end of the castle, at its foundation. Here, we could see the transition from the natural stone below.

We followed the route to a small patio area at the southwest corner of the fortress.

The restaurant here was closed but the gate to the patio was open. We had a fantastic view of the scene to the south from here!

Looking to the west, we could see the city wall that extends from the fortress.

We continued on up into the fortress. It wasn’t really clear where we should head to next. We walked to the east, finding a gift shop and arsenal, which serves as a museum. The shop keeper told us that we should head to the Prince’s Chambers, also referred to as the Royal Apartment, as it would be closing at 11am today, in less than 30 minutes! So, we rushed back to the west to find the entrance.

The first room is the Golden Hall. A sign describes the room:

The Golden Hall served as a ballroom. The magnificent ceiling of the wood-panelled space is supported by four mighty twisted marble columns. On a beam and on three walls there are numerous coats of arms of the kingdom, of powerful German cities, and also the bishoprics affiliated with Salzburg. Four marble Gothic portals lead to adjacent rooms and apartments.

The next room, to the right, is the Golden Chamber. This elaborately decorated item is a furnace! A sign provides some background:

The Golden Chamber is the most richly decorated room. It was heated by the means of a magnificent tiled stove and served as the setting for official receptions and as a living space. In the intricately and extravagantly executed furnishings the roles of Leonhard von Keutschach as imperial prince and religious dignitary are united. The stove is a rare and valuable example of Late Gothic ceramic craftmanship. The stylistic elements of the outgoing Gothic are combined with those of the approaching Renaissance. A door leads into the small library. This served as a study. Tendril paintings, enriched with flowers and a few individual figural elements, characterize the appearance of the Golden Room.

Unfortunately, the room was undergoing restoration activities resulting in the library being inaccessible.

One of the walls in the room. A large sign in the middle of the room explains the renovations taking place here:

The Golden Chamber has been undergoing extensive restoration work since the summer of 2017 Phase I of the restoration has already been completed (the north wall wall with access to the bedroom, part of the east oriel) and the project is now in phase II (part of the south wall, as well as the south and east oriels). Phase ill will then restore the rest of the south oriel and the remaining south wall and west wall in the final phase (IV), the work will focus on the areas around the tiled stove. Both the walls and ceilings are being restored in equal measure. Any removable parts sculptures, reliefs) will be taken away and worked on in the studio (during the winter).

Concept and supervision: Atelier Prenner-Scheel (Ilse Prenner, Elisabeth Scheel), Vienna

Execution: Salzburger Burgen & Schlösser, Restauration Division (Florentina Woschitz and her team)

In collaboration with the Austrian Federal Monuments Office (BDA) in Salzburg (Director Eva Hody)

General

The Golden Chamber was built in 1501 under Prince Archbishop Leonhard von Keutschach, it forms part of the princely chambers ("Furstenzimmer") and is the most sumptuous of the Three rooms. The Golden Chamber features do le laver panelling made of Swiss pine and is richly decorated with gilded and colourful carvings.

At the time they were built, the ceiling and the upper half of the walls were also coated in precious azurite (deep blue copper pigment).

Renovation history

Over the centuries the original structure from 1501 hat been renovated multiple times, from the gilded and painted carvings, to the blue colour of the surfaces.

Thus, the ceilings and walls are now covered in five different shades of blue.

From bottom to top:

Azurite (original, 1501)

Natural ultramarine (ca. late 16th or 17th century)

Synthetic ultramarine (1851, extensive restoration by the artist and architect Georg Petzolt)

Sky blue 'Coelin blue' (1946-49, restoration by sculptor Jakob Adlhart)

Turquoise-blue synthetic pigment mix (1957-58, restoration by church painter and restorer Josef Watzinger) - currently visible version

The next room was the bedchamber. A sign here reads:

The bedchamber is the most private room of the Royal Apartment. In contrast to the Golden Hall it has no tiled stove. There is nothing left of the original furniture. Behind the door is hidden a toilet, a so-called "garderobe", which for the times was a very advanced construction accessible from all floors.

The toilet.

A window provides a view to the north. We could see the entire old town area below us as well as portions of the city wall on the opposite side of the Salzach.

We had skipped this first room just beyond the entrance to the Prince’s Chambers but visited it on our way out. It contains the Magic Theater. This audio and visual room provides some history about Salzburg and the castle.

The rooms below the Prince’s Chambers currently house museum spaces, in particular the Rainer Regimental Museum, named after the Archduke Rainer Ferdinand.

The museum held many historical artifacts related to the unit. We quickly walked through.

We had a nice view from one of the windows.

The museum ends with a World War I display.

We continued on, walking through a kitchen area in the fortress.

As we continued past the kitchen, we had some nice views of the castle’s interior spaces as well as the old town below to the north.

We entered a small chapel that was devoid of the typical Christian religious items but did have an art installation. A sign explained:

Heaven on Earth

Gerold Tusch (*1969)

2017

Installation, Ceramic, Aluminum

In the spatial installation "Heaven on Earth", Gerold Tusch shows rings of clouds with an ornamental effect.

Here, Tusch is alluding to the motif of the "Silver Cloud". The motif crops up in Baroque illusion painting and on altarpieces.

In this way, Gerold Tusch gives significance to a disregarded embellishment in Christian art and puts it centre stage.

We came across an elaborately decorated stove:

Tiled stove with the "7 Liberal Arts and Planets", pictured as human beings

Workshop Thomas Strobl (+1622)

Salzburg, around 1570

The stove is made of large tiles with colourful glazing. The stove is an important masterpiece from the ceramic and stove-setter workshop of Thomas Strobl. Thomas Strobl's ceramic workshop made stove tiles and vessels. In the 16th and 17th centuries the workshop was located on Steingasse in Salzburg. The tiles with shell niches show the "Liberal Arts and Planets". The crowning top and the feet in lion-paw form are now lost.

There was also a bed with canopy from 1675. No details were provided.

There was also a table, with marble inlay, and four chairs dating from 1688. A few details were provided:

The table has a foot board for resting the feet.

This foot board is often seen on tables from the Alpine region.

The table has a top made of marble from Adnet.

Adnet is a village south of Salzburg.

There are quarries with red marble.

The chairs have the symbols of St. Peter's Abbey on their backs.

The symbols are 2 keys and a mitre.

A mitre is a kind of hat which the Pope wears.

Interestingly, the language used as well as spacing on this sign was extremely basic, as if made for a 1st grader. The German and Italian text seemed to be similar.

There was an old archway that was discovered inside of a wall. A sign explains:

The Chamber of Frisinger

The round-arched arcade was discovered during renovations in 1998.

The arcade has 6 arches.

The arcade is colorfully painted.

The arches were the windows.

Originally the arches were open.

They were placed in an outside wall of the castle.

The outside wall belongs to the oldest part of the castle.

This part is called the "Palais" - palace.

Archbishop Konrad von Abensberg (1106-1147) ordered this building to be put up.

On the opposite side there was also a round-arch arcade.

These arches can no longer be seen today.

In the 16th century the office of the "Pfleger" was located in this room.

The "Pfleger" was the manager of the castle.

Kept in the cupboards, chests and tables were work materials, bills, books on law and lists for the Hohensalzburg Fortress bookkeeping.

Once again, very simple language on this sign.

We continued past more windows showing the complex structure of the castle in the foreground.

There was a small exhibit showing some historical coins.

We passed by an area which showed ruins of previous structures here at the fortress.

This old well was closed shut.

At this point, we weren’t sure exactly where to go next. We ended up at a section of the fortress with a large outdoor plaza below us and some stairs leading up to where we were. From here, it seems the funicular is somewhere below and to the left. We likely would have ended up here if we turned left after getting off the funicular. We decided to turn around rather than go down.

We found an entrance that leads to the funicular!

We ended up at the entrance to the Panorama Tour. This is a series of rooms, passageways, and towers that goes around the upper fortress walls.

We picked up a pamphlet with some information about the route.

The first room we entered, the Salt Depot, had a salt model of the fortress and old town area below. From there, we headed into and up the Prison Tower.

The square top of the Prison Tower had a fantastic view! This tower is at the western edge of the fortress and almost directly above the funicular. We took photos at 45° intervals, starting from the east and going counter clockwise.

The tower has a little elevated platform at the center.

After exiting the tower, we continued on the route.

We took a quick look at St. George’s Church.

We continued walking along the periphery of the fortress. It isn’t clear if we really followed the entire route as depicted on the Panorama Tour pamphlet.

We went back to the first building that we visited in the morning, the arsenal. We took a quick look around. There wasn’t anything that we found particularly interesting as armor, swords, and cannon are rather common in museums.

We looked up to see the Prison Tower as we headed to find something to eat for lunch. The fortress, being on a hill above town, has very limited food options. We didn’t want to head back down as we were planning on walking the Mönchsberg, a hill adjacent to the fortress.

We decided to eat at the Panoramarestaurant zur Festung Hohensalzburg, one of the castle’s two dining options. The ratings weren’t particularly great but it was better than the other restaurant. The Panorama Restaurant, in addition to being a full restaurant inside a fortress building, also seems to operate the patio area where we took photos from earlier in the morning right after arriving.

We had a nice view from our table.

We decided to order an eiskaffe, something that didn’t seem to be particularly popular or easy to find in Munich, though maybe we just weren’t at the right places to find it. This restaurants rendition of this normally delicious and reliable treat was rather disappointing with no real coffee flavor.

We decided to try the veal sausage. The sausage was OK though nothing particularly special.

We also ordered the mountain peak shaped Salzburger Nockerl, a local sweet souffle. The souffle was mostly good but the texture varied. It sits on a base of berry sauce, unfortunately inconsistently applied so that it was only present on maybe ⅓ of the total area.

Overall, a disappointing meal. Service was also very slow despite this restaurant having few customers and an excess of servers. Unfortunately, there were no real alternatives that didn’t involve going back down into town.

After lunch, we went to exit the fortress to the west. It wasn’t really obvious exactly how to this. The funicular is on the west side of the fortress but there is no other exit.

It looked like the only pedestrian exit was to the east. So, we walked in that direction.

We found a passageway near the arsenal. Was this really the right way to go?

It turns out that it was, though there also seemed to be an alternative staircase to reach the path out.

We followed the path as it looped around the fortress’ north side. The path descended rather steeply.

This part of the fortress wall spanned a little ravine with an opening below the wall.

We definitely ended up lower than we expected! We could see the fortress high up above us now. We ended up right above the midpoint of the funicular which passed below us.

Mönchsberg

We don’t know officially where the Festungsberg (Fortress Mountain) ends and the Mönchsberg (Monk Mountain) begins. But, the lowest point between the two hills seems like a reasonable border between the two. And the lowest point was now behind as as we continued walking to the west.

This area seemed to be a mix of parkland, isolated residential style buildings, older castle structures, and various portions of the remaining fortress wall.

We passed by this tower, the Freyschlössl, also known as the Roter Turm (Red Tower). According to the German language Wikipedia article, the tower dates back to the 13th century and is currently private property.

There is a nice view of the fortress from the path by the tower. While we had ascended a bit along the path, we were still well below the fortress.

We passed by a museum, the WasserSpiegel. This museum provides information about Salzburg’s water supply and is located at a reservoir. This seems to be an underground reservoir as there is no pool of water visible on Google Maps’ satellite view. We don’t really know if this museum would have been an interesting place to visit. But, given the time, we continued on.

We came upon a hill just past the museum. A path seemed to lead up the hill to a section of fortress wall. We decided to take a look.

The path was paved but isn’t visible in this photo. The vehicle tracks running through the grass are unrelated.

A little pond came into view as we walked along the path up.

As we approached the top of the path, we could see the fortress starting to come into view.

Soon, we saw the fortress above the section of wall at the side of the hill!

In the opposite direction, we could see a lake, suburban style buildings, and the snow capped mountains beyond.

This was as far as we could go on the path.

This tower, the Josefsturm, was here at this point. It is surrounded on 3 sides by wall. A sign explains this defensive position, the Richterhöhe Fortification:

This strategically important part of the Mönchsberg was settled by Stone Age hunters 5000 years ago, fortified in 1367, reinforced to become a major component of the defence during fortifications during the Thirty Years' War (1618-48), changed into an arsenal in 1724; and finally, in 1906, named after the famous geographer and mountaineer Prof. Eduard Richter and opened to the general public.

When Salzburg was turned into an impregnable fortified city during Thirty Years' War, the Richterhöhe gained a major role. Here, the strategically ingenious defence system ended, which closed the open southern flank of the Mönchsberg: From the Hasengraben bastion (part of the Fortress) to Scharten gate and the Katze (Cat) below, then a 200 m (218 yd) long massive wall to the west (Bürgermeisterloch = "Mayor's Hole") to the perpendicular cliff, finally to Richterhöhe via the Zwinger (bailey).

The bailey blocked an easily accessible dip and also functioned as a sally port. The bailey was a walled square with two gates. In case attackers entered through the (lower) gate, they came under massive fire from four walls. This worst-case scenario never happened. Instead, wine was grown in this climatically protected depression. Of the old defence system the gunpowder magazines (Josef's Tower and Michael's Tower), the bailey's gate towers survive into modern times. The Kuppelwieser Schlössl was built where a former tower stood.

Dr. Clemens Hutter

The view showing the top of the wall to the south.

This stone is a monument to Eduard Richter, an Austrian geologist. This location, the Richterhöhe (the English would probably be something like Richter Heights), was named after him1.

We backtracked to return to the path that we were on before this little detour. We passed by this tree with many little berries.

We continued on the path, which now curved to the north. We reached a long viewing platform, perhaps best described as a long section of path with a clifftop fence, which had views of the cityscape to the west of the Mönchsberg.

A nearby sign describes the Rainberg, the small forested mountain, or hill, that can be seen on the left of the photo:

The Rainberg hill and its present appearance was strongly influenced by quarrying during the 19th and 20th centuries, when wide areas of the rock formation were destroyed. Nevertheless, the original structure with a smaller, upper eastern part (Upper Rainberg) and a larger, lower western part (Lower Rainberg) persists.

The Rainberg used to be surrounded by bogs on three sides, from which the Mountain rose like a natural island fortress with rock precipices. Access was only possible from the east via the saddle of Buckelreuth. Due to its natural protection, the Rainberg was an ideal place for prehistoric settlements.

A large number of artifacts - discovered mainly during quarrying - point towards continuous settlement from the 5th millennium B.C. to about 0 A.D. Some characteristic stone tools even indicate the use in the Mesolithic Age. The prehistoric settlements on the Rainberg blossomed especially during the Early and Late Neolithic Age, at the turn from Bronze Age to Iron Age (Hallstatt period) as well as in the late Celtic period (La Tène period).

The Rainberg contains the oldest human habitation within the City of Salzburg. The supra-regional significance of the location Rainberg is emphasized by the long period of habitation, by the large number of artefacts, as well as several outstanding beautiful pieces, which indicate far-reaching trade relations and corresponding prosperity.

We continued on, reaching a point where we could look out to the east. From here, we could see the historic section of Salzburg below us.

Soon, we reached this section of wall that runs atop the Mönchsberg. It looked like parts were boarded up for winter.

There is a restaurant and hostel at the northern end of the wall, right above the town below. From the edge of the outdoor patio, we could see the old town below and the fortress above!

We created a panorama of the scene from here.

We walked through a gate, more like a doorway, through the wall.

We walked to the north on the west side of the wall.

We once again had a fantastic view, though similar to what we saw from the patio on the east side of the wall.

There was nowhere to go at the northern end of the wall. So, we walked to the south where we saw a path heading away to the west.

We reached a gate through the wall, opposite of the path where we were headed.

This was at the southern end of this section of wall. From here, we could see to the southwest.

We came from the path on the right next to the wall. We continued on the path that runs through the tunnel.

We soon reached the Museum der Moderne Salzburg, an art museum. By now, it was almost 3pm. No time for the museum! We instead headed down to the town below by the MönchsbergAufzug, an elevator.

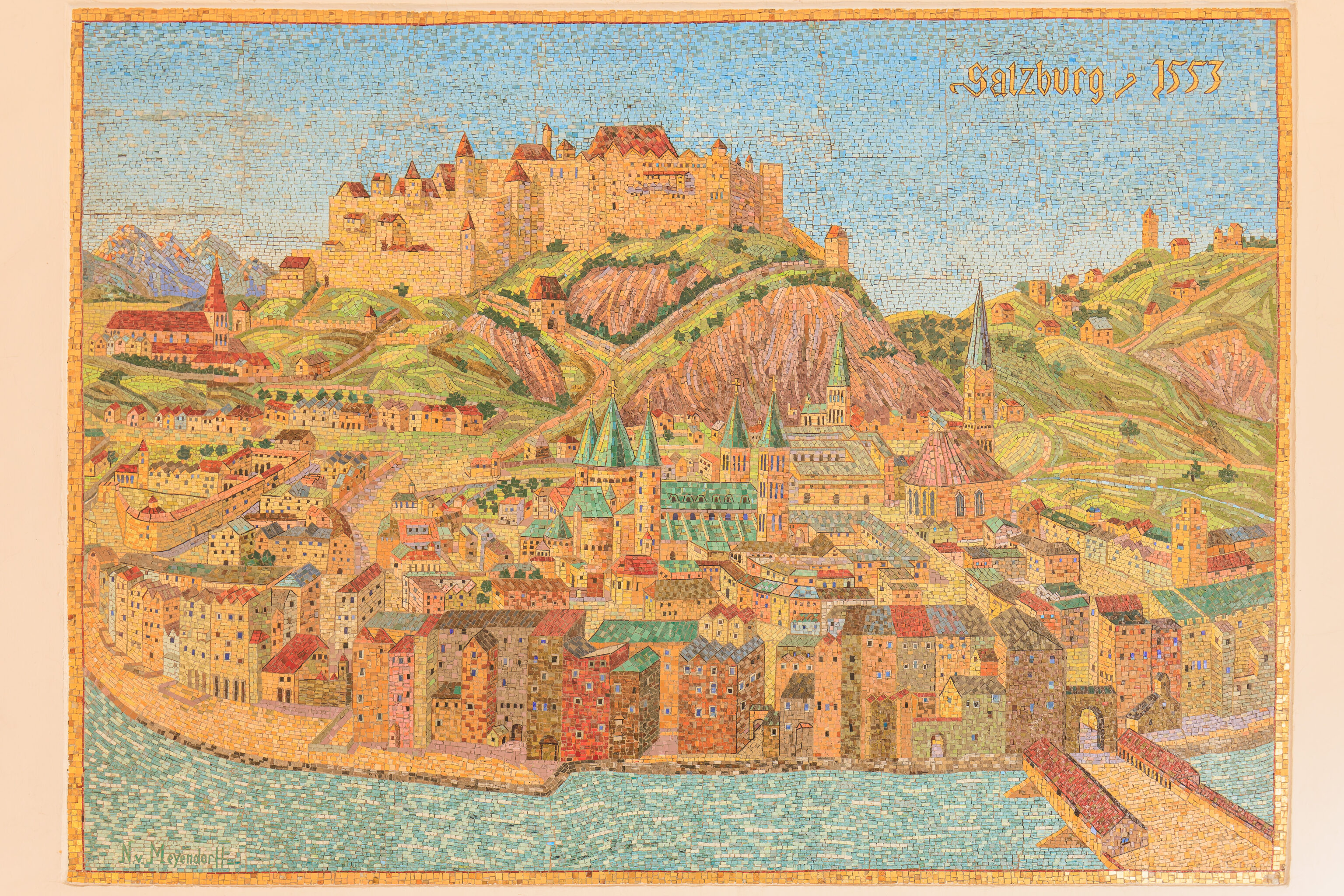

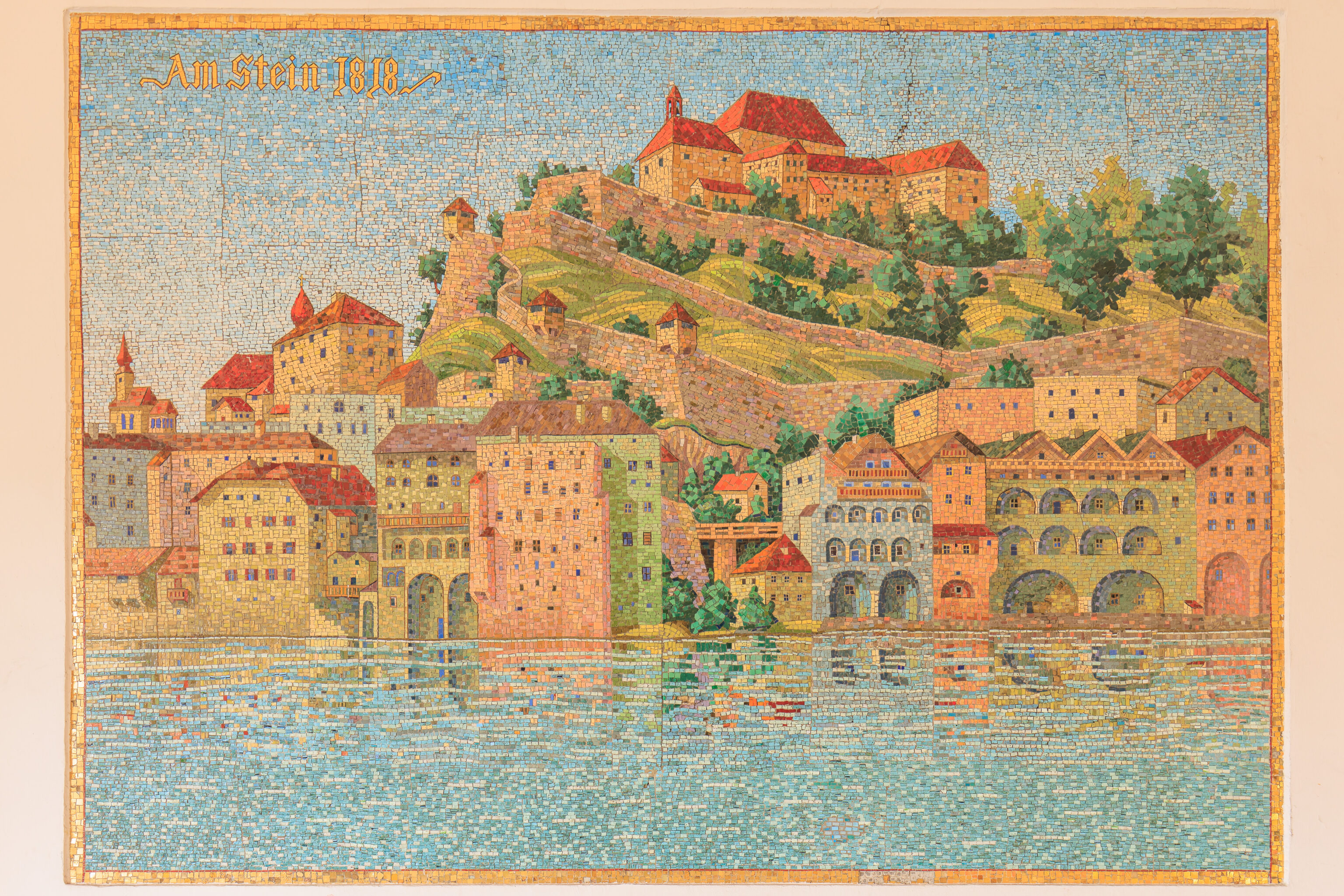

These two tiled works of art were at the base of the elevator.

Mozart Museums

Salzburg is the birthplace of the renowned composer, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. So of course, we had to visit a Mozart museum! There are two that we wanted to visit, the Mozarts Geburtshaus (Birthplace) and Mozart-Wohnhaus (Residence). They both close at 5:30pm so we didn’t have much time. But, luckily they were both nearby!

Mozart’s Birthplace was closer to where we were, just a few minutes away by foot. So, we started heading in that direction.

We briefly stopped at the Balkan Grill Walter, a tiny shop that created and still sells Bosna, something that has become a local specialty. We got the original, which is two sausages on bread with a variety of spices and curry. There was a long queue, though it passed fairly quickly. It was a nice snack, definitely better than the lunch food that we had earlier!

One of the decorations on a building that we walked by.

We quickly reached Mozart’s Birthplace! It was pretty busy outside as there was a tour group moving through.

After entering the building, we walked upstairs to reach the apartment where Mozart was born. A sign, titled Living Situation, provided some basic information:

In 1747 the young "High Princely Salzburg Chamber Musician" Leopold Mozart and his wife Anna Maria Walburga moved into the third floor of this house. The Mozart Family lived in this rented apartment for 26 years. It consisted of a kitchen, small store room, living room, bedroom (birth room) and study. Seven children were born here but only two survived to adulthood: Maria Anna Walburga, known as "Nannerl", was born in 1.751, and on 27 January 1756 Wolfgang Amadeus was born. In 1773 the Mozart Family moved into a larger apartment in the so-called "Dancing Master's House" on the Makartplatz.

The museum had quite a bit of informational text written on the walls to read. One described Mozart’s father:

Johann Georg Leopold Mozart (1719-1787) was born on 14 November 1719 as the son of the master bookbinder Johann Georg Mozart in Augsburg. After completing an excellent classical training in Latin, Greek and music at the Jesuit College Leopold decided against studying theology and in 1737 moved to Salzburg where he studied philosophy at the Benedictine University He provoked his dismissal from the university and in 1740 entered service as valet and musician to the canon Johann Baptist Graf Thurn-Valsassina und Taxis. In 1743 Leopold became a member of the court orchestra of the Salzburg prince-archbishop and violin teacher in the chapel house. In 1757 he was appointed as court composer and in 1763 finally became deputy conductor. In 1747 he married Anna Maria Walburga Perti in Salzburg Cathedral. The marriage lasted over thirty years and was very happy.

Until 1760 Leopold Mozart was enthusiastically engaged in teaching and composing. He became well known throughout Europe in 1756 because of his revolutionary textbook Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Playing the Violin. After 1760 Leopold devoted himself increasingly to teaching his two child prodigies and undertook extensive study tours and to give concerts in the musical centres of Europe. In later years Leopold continued to keep a watchful eye on his children as can be seen by the great number of letters they exchanged.

Leopold Mozart died on 28 May 1787 in the Dancing Master's House on the Makartplatz in Salzburg.

Leopold Mozart was an outstanding personality in his lifetime; he was discerning, highly educated intellectual and had a sophisticated bearing.

There was similar text describing Mozart’s mother:

Anna Maria Mozart, née Pertl (1720-1778) was born on 25 December 1720 in St. Gilgen. As the daughter of the district administrator and judge Wolfgang Nikolaus Pertl, she spent the first years of her life in the court building in St. Gilgen.

After the sudden death of her father in 1724, she moved with her mother Eva Rosina and her older sister, who died soon afterwards, to Salzburg where she lived on a small mercy pension.

On 21 November 1747 Anna Maria married the court musician Leopold Mozart in Salzburg Cathedral and moved with him into the apartment on the third floor of what is now Getreidegasse No. 9. It was a love wedding and they had a happy marriage. During the first nine years she bore seven children, of whom only two survived. These two "Nannerl' and Wolfgang, who was five years younger, were to determine the course of her life.

She accompanied her husband and their two children on the early concert tours and became acquainted with other countries, royal courts, customs and languages. Mozart's mother always remained in the background but she brought harmony and warm-heartedness into the artistic household and ensured that it functioned well. Her life between her authoritarian and stubborn husband and her genius son, who was in a world of his own, was certainly not easy. At the request of her husband she accompanied Wolfgang on his journey to Mannheim and Paris, from where she was not to return. She died on 3 July 1778 at the age of 57 alter a brief illness in Paris.

Anna Maria Mozart was popular everywhere. Besides being endowed with a good portion of common sense, she was also conscientious, kind and had a great sense of humour.

We continued on to read a description of Mozart’s sister:

Maria Anna "Nannerl" Mozart (1751-1829) was born during the night from 30 to 31 July 1751 in this house. From the age of seven she received piano lessons from her father Leopold, court musician and music teacher, who recognised and encouraged her extraordinary talent. Together with her parents and her highly talented musical brother Wolfgang, she travelled across half Europe from 1763. They were celebrated as the child prodigies from Salzburg at all the major princely and royal courts.

As a young man Wolfgang continued to go on concert tours with his father but from the age of seventeen Nannerl had to stay behind in Salzburg. She began to give piano lessons, and also performed successfully as a pianist among circles of friends and acquaintances. After the death of her mother and the departure of her beloved brother to Vienna, Nannerl managed the household for her father in their home in the Dancing Master's House.

In 1784, at the age of 33, she married Johann Baptist von Berchtold zu Sonnenburg who had been widowed twice and was the father of five under-age children. He was the judge in St. Gilgen and thus a successor in office to her grandfather.

Nanneri took over the household in her mother's birthplace in St. Gilgen. She bore her husband three more children but only the son Leopold reached adulthood. In 1801, after the death of her husband, Nannerl moved back to Salzburg where she again gave piano lessons.

Nannerl died on 29 October 1829 and was buried in a municipal crypt in St. Peter's cemetery.

Nannerl Mozart was an excellent pianist and as a woman and musician of the 18th century she was always overshadowed by her brother.

And finally, the most famous member of the Mozart family:

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) was born on 27 January 1756 in this house. His father discovered his extraordinary musical talent at an early age and he knew best how to encourage it. At the age of five Wolfgang could already play the violin and piano. In 1761 he performed in public for the first time and one year later his father embarked with him on the first of several concert tours in order to make the child prodigy well known in Europe. At the age of eight Wolfgang wrote down his own first compositions himself; he composed his first work for the stage at the age of eleven.

From 1769 to 1773 he celebrated great successes in Italy. At the age of sixteen he was appointed concert master of the Salzburg court orchestra. In 1777 he first requested permission from Prince-Archbishop Colloredo to leave the orchestra so that ne could again travel. Mozart hoped to be appointed as a composer at one of the great European royal courts. The attempt failed, he returned to Salzburg and was given an appointment as court organist.

In 1781, at the age of twenty-five Wolfgang broke away finally from his employer and settled in Vienna. One year later he married Constanze Weber. The couple had six children, of whom only two sons lived to adulthood. In 1787 Joseph II appointed Mozart as Imperial and Royal Chamber Musician. Wolfgang lived until his death in 1791 as a freelance composer, pianist and music

teacher. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart spent about one third of his life, in fact 3,720 days travelling. In the 35 years of his life he composed over 600 musical works, including 22 operas.

"A phenomenon such as Mozart always remains a miracle that cannot be explained further." (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1831)

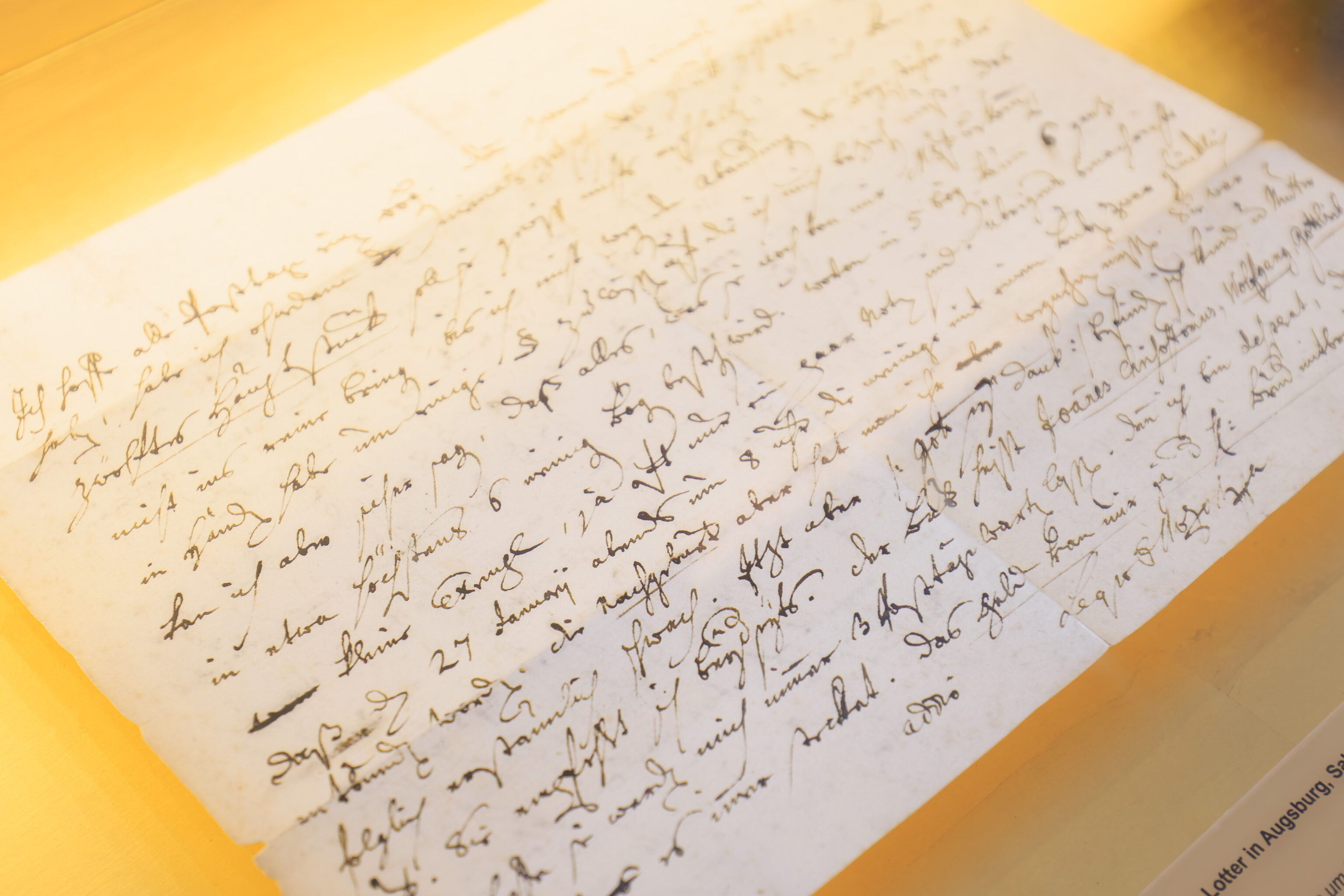

The writing above is a copy of a letter written by Mozart’s father announcing the birth of his son:

Letter from Leopold Mozart to Johann Jakob Lotter in Augsburg, Salzburg, 9 February 1756 Facsimile

"By the way I have to report that on 27 January at 8 o'clock in the evening my wife was fortunately delivered of a little boy. The afterbirth had to be taken away from her and so she was extraordinarily weak. Now, however, thank God, both child and mother are doing well. She sends her regards. The boy is called Joannes Chrisostomus, Wolfgang, Gottlieb."

There were a few paintings, like this one, on display.

This is the room where Mozart was born! Unfortunately, it is mostly just an empty room with a few displays inside.

This is a violin that Mozart received when he was six. A sign provides some detail:

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's child violin

Made by Andreas Ferdinand Mayr, Salzburg 1746

Mozart received his child violin at the age of six and a half in the autumn of 1762. The size of the instrument corresponds to a violino piccolo which measured between a quarter and a half violin. By the age of five, Mozart could already play piano and violin.

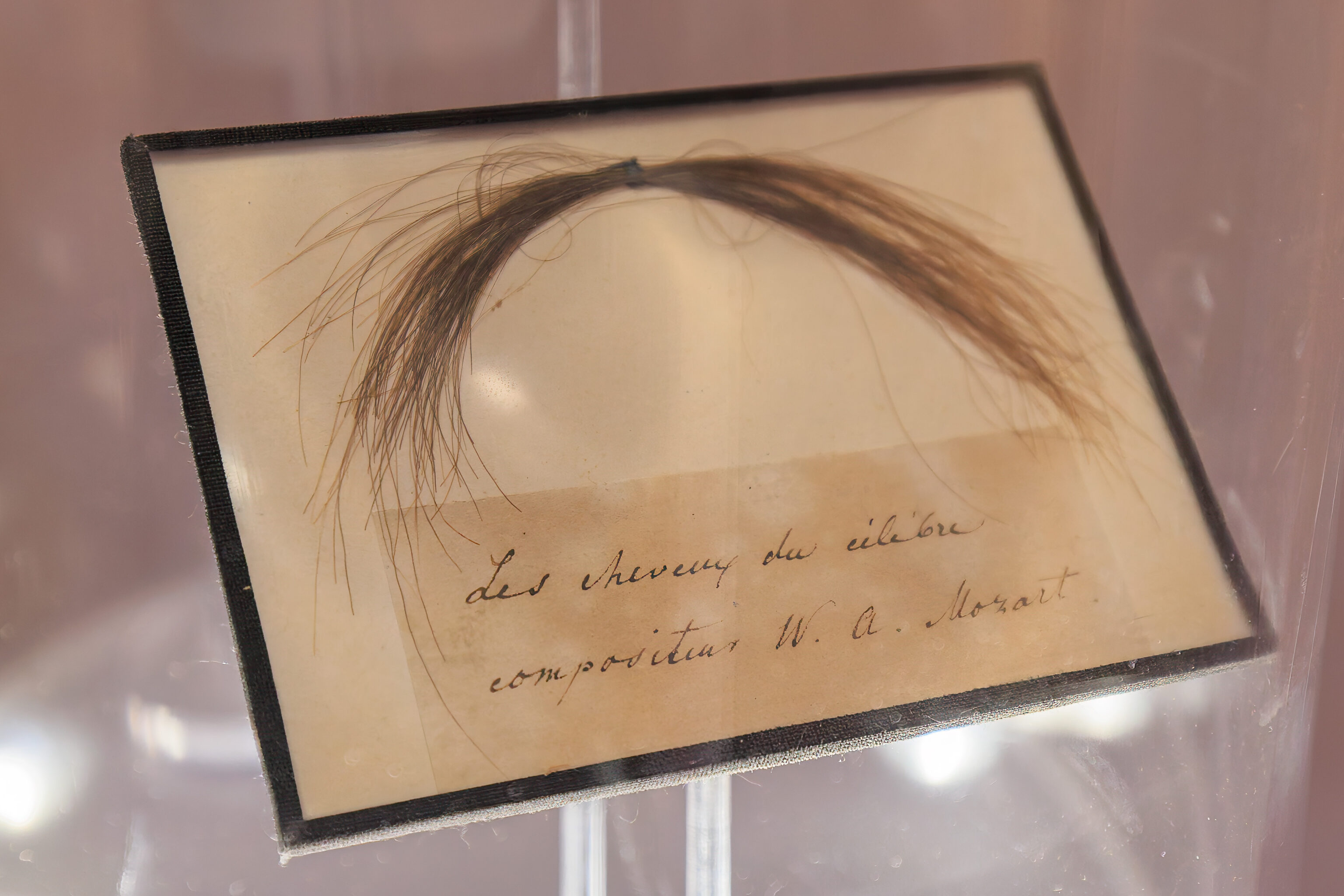

There were various other small items on display but perhaps the most interesting, and slightly odd, is Mozart’s hair. A sign explains this item:

The International Mozarteum Foundation owns four locks of hair which are ascribed to Wolfgang Amadé Mozart. The only result of a genetic analysis showed that three of the four locks came from the same person.

This tiny portrait is supposed to be the most realistic one of Mozart. A sign explains:

Silverpoint drawing by Doris Stock, Dresden, April 1789

This portrait is the most authentic depiction of Mozart. It was created two and a half years before his death. Mozart was travelling in Germany and in Dresden he became acquainted with the painter Doris Stock.

This piano doesn’t have much of a description, presumably, it belonged to Mozart. A sign provides a bit of information on its history after his death:

Small square piano, probably from the possessions of Constanze Mozart, Early 19th century

On permanent loan from Konstantin Hiller, Salzburg Konzertgesellschaft

According to reports the instrument was sold by Constanze Mozart in 1820 in Copenhagen to the clarinettist Cari Gottlob Füssel, a great admirer of Mozart. In 1899 the piano was acquired by the Danish painter Peter listed (1861-1933) who left it to his son-in-law Peter Olufson, in whose family the instrument remained until 2006.

These costumes, from 2018, are for one of Mozart’s operas, The Magic Flute.

We exited the museum not long after 4pm and started walking over to the Mozart Residence.

The residence is on the north side of the Salzach. We crossed via a pedestrian bridge to the west. From the bridge, we could see some of the fortifications on a hill across from the Hohensalzburg Fortress.

We could also see the fortress up on its hill above the old town.

There were many locks attached to the bridge.

The view from the northern end of the bridge, looking to the east.

The Mozart Residence was just a block away from the bridge. Like the previous museum, there were various panels of text to read. One provided a brief description of Mozart’s time here in this building:

Wolfgang Amadé Mozart (1756-1791) lived seven years, until the end of 1780, in this house. Most of his Salzburg compositions originated here.

In the Dancing Master's House, Wolfgang Mozart composed three operas: "La finta giardiniera" (1774), "Il re pastore" (1775) and "Idomeneo, re di Creta" (1780). From here, in 1777, he embarked on a journey to Paris with his mother, Anna Maria. From this journey he returned alone. His mother died of typhoid on July 3, 1778 in Paris. Her death was a blow to the entire family.

After a sojourn in Munich for the premiere of "Idomeneo", he did not return to Salzburg, and instead relocated to Vienna in 1781. Two years later he returned with his wife Constanze on a 3 month visit in the Dancing Master's House.

Mozart’s father lived here until his death:

Leopold Mozart (1719-1787) lived in this house until his death on May 28, 1787.

After the death of his wife in Paris and Wolfgang's move to Vienna, Leopold lived after 1781 with his daughter Maria Anna (Nannerl) in the Dancing Master's House.

Together they played Wolfgang's compositions and went to the theatre and opera, in addition to visiting university lectures in experimental physics.

In the 1780s, Leopold took three boarding pupils into his household. Among them were both children of his Munich-based friend Theobald Marchand. Heinrich and Margarethe Marchand received a fundamental musical education from Leopold.

Mozart’s sister lived here until she married:

Maria Anna Mozart (1751-1829) more commonly known as "Nannerl", lived here until her marriage in August, 1784.

At 33, she married a judge from St. Gilgen, Johann Baptist von Berchtold zu Sonnenburg. She was a highly talented pianist and piano teacher. She managed the household of her father after her mother's death and her brother's departure to Vienna.

Her first son, Leopold, was born in 1785 in this house, and lived here, being lovingly cared for by his grandfather, until Leopold Mozart's death.

She documented her daily routine in and around this house in a diary for eight years.

This piano belonged to Mozart and was used in various performances in Vienna.

Presumably, this instrument was used by Mozart, though we failed to photograph its sign.

This portrait of Mozart is from when he was thirteen. A large sign provides some detail:

HISTORY IS MADE IN VERONA: A MOMENT CAPTURED FOR ETERNITY!

Attributed to Gianbettino Cignaroli (1706-1770):

Mozart in Verona, oil on canvas, Verona, January 6-7, 1770.

Loan from a private collection.

The wealthy Veronese Pietro Lugiati, a financial official of the Republic of Venice, was very impressed by Mozart's musical abilities, and asked Leopold Mozart for permission to have his son painted. The artist met with thirteen-year-old Mozart at Lugiati's palazzo in Verona. According to a letter Leopold Mozart wrote to his wife in Salzburg on January 7, 1770, Mozart sat for the painter twice. Leopold does not refer to the painter by name in this letter, although he later mentions the painter Cignaroli in his travel notes. An article published just a few days later in the Gazzetta di Mantova announced that Mozart was being painted life-size to be remembered for eternity. The verse on the painting's ornate original frame expresses the admiration felt for Mozart.

This portrait is of an older Mozart doing the hand in shirt thing. The sign to the right describes this work, which is a reproduction of the original painting:

Attributed to Johann Nepomuk della Croce (1736-1819): Mozart as Knight of the Golden Spur. Oil on canvas, 1777. Copy by Giuseppe Nardi, Bologna 1926. International Mozarteum Foundation, Mozart Museums.

Mozart is depicted here as a proud Knight of the Golden Spur, as shown by the star on his chest. He was awarded the order by Pope Clement XIV in Rome on July 5, 1770, an unprecedented honor for such a young musician. The portrait of Mozart was painted for Mozart's patron Padre Martini (1706-1784). Padre Martini created a stately gallery of 300 portraits of musicians. Mozart's portrait as a Knight of the Golden Spur was also to find its place here. It is believed that Johann Nepomuk della Croce, who worked in Burghausen, executed the oil painting that Mozart's father sent from Salzburg to Padre Martini in Italy in November 1777.

Unfortunately, we didn’t photograph the sign for this ornately decorated piano.

This room at the end of the route contained a model of the residence as well as some facts and figures related to Mozart.

We left the museum at around 5pm, about 30 minutes before the 5:30pm closing time. We caught a bus to return to the Hauptbahnhof.

We had a bit of extra time until the next train to Munich so walked around the station a bit.

We could see mountains in the distance from the platform.

Other than the mountains, there wasn’t much to see from the station. The trip back to Munich was uneventful, though we did have a longer than scheduled stop at Freilassing, the first town in Germany right next to Salzburg, for some unknown reason.